The Smart City - City of Knowledge

From Mondothèque

Revision as of 16:56, 26 February 2016 by Dickreckard (talk | contribs)

Contents

[hide]Formulating the Mundaneum

“We’re on the verge of a historic moment for cities” [2]

“We are at the beginning of a historic transformation in cities. At a time when the concerns about urban equity, costs, health and the environment are intensifying, unprecedented technological change is going to enable cities to be more efficient, responsive, flexible and resilient.”[3]

In 1927 Le Corbusier participated in the design competition for the headquarters of the League of Nations, but his designs were rejected. It was then that he first met his later cher ami Paul Otlet. Both were already familiar with each other’s ideas and writings, as evidenced by their use of schemes, but also through the epistemic assumptions that underlie their world views.

Before meeting Le Corbusier, Otlet was fascinated by the idea of urbanism as a science, which systematically organizes all elements of life in infrastructures of flows. He was convinced to work with Van der Swaelmen, who had already planned a world city on the site of Tervuren near Brussels in 1919.[4]

For Otlet it was the first time two notions from different practices came together, namely an environment ordered and structured according to principles of rationalization and taylorization. On the one hand, rationalization as an epistemic practice that reduces all relationships to those of definable means and ends. On the other hand, taylorization as the possibility to analyze and synthesize workflows according to economic efficiency and productivity. Nowadays, both principles are used synonymously: if all modes of production are reduced to labour, then its efficiency can be rationally determined through means and ends.

“By improving urban technology, it’s possible to significantly improve the lives of billions of people around the world. […] we want to supercharge existing efforts in areas such as housing, energy, transportation and government to solve real problems that city-dwellers face every day.”[5]In the meantime, in 1922, Le Corbusier developed his theoretical model of the Plan Voisin, which served as a blueprint for a vision of Paris with 3 million inhabitants. In the 1925 publication Urbanisme his main objective is to construct “a theoretically water-tight formula to arrive at the fundamental principles of modern town planning.”[6] For Le Corbusier “statistics are merciless things,” because they “show the past and foreshadow the future”[7], therefore such a formula must be based on the objectivity of diagrams, data and maps.

Moreover, they “give us an exact picture of our present state and also of former states; [...] (through statistics) we are enabled to penetrate the future and make those truths our own which otherwise we could only have guessed at.”[8] Based on the analysis of statistical proofs he concluded that the ancient city of Paris had to be demolished in order to be replaced by a new one. Nevertheless, he didn’t arrive at a concrete formula but rather at a rough scheme.

A formula that includes every atomic entity was instead developed by his later friend Otlet as an answer to the question he posted in Monde, on whether the world can be expressed by a determined unifying entity. This is Otlet’s dream: a “permanent and complete representation of the entire world,”[9] located in one place.

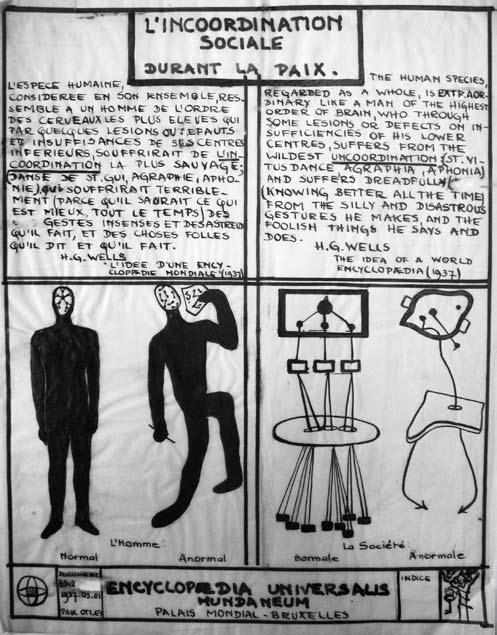

Early on Otlet understood the active potential of Architecture and Urbanism as a dispositif, a strategic apparatus, that places an individual in a specific environment and shapes his understanding of the world.[10] A world that can be determined by ascertainable facts through knowledge. He thought of his Traité de documentation: le livre sur le livre, théorie et pratique as an “architecture of ideas”, a manual to collect and organize the world's knowledge, hand in hand with contemporary architectural developments. As new modernist forms and use of materials propagated the abundance of decorative elements, Otlet believed in the possibility of language as a model of “'raw data'”, reducing it to essential information and unambiguous facts, while removing all inefficient assets of ambiguity or subjectivity.- The part "]]" of the query was not understood. Results might not be as expected.

- Some subquery has no valid condition.

[[category:{{{1}}}]] “Information, from which has been removed all dross and foreign elements, will be set out in a quite analytical way. It will be recorded on separate leaves or cards rather than being confined in volumes,” which will allow the standardized annotation of hypertext for the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC).[11] Furthermore, the “regulation through architecture and its tendency of a total urbanism would help towards a better understanding of the book Traité de documentation and it's right functional and holistic desiderata.”[12] An abstraction would enable Otlet to constitute the “equation of urbanism” as a type of sociology (S): U = u(S), because according to his definition, urbanism “is an art of distributing public space in order to raise general human happiness; urbanization is the result of all activities which a society employs in order to reach its proposed goal; [and] a material expression of its organization.”[13] The scientific position, which determines all characteristic values of a certain region by a systematic classification and observation, was developed by the Scottish biologist and town planner Patrick Geddes, who was invited by Paul Otlet for the 1913 world exhibition in Gent to present his Town Planning Exhibition to an international audience.[14] What Geddes inevitably takes further is the positivist belief in a totality of science, which he unfolds from the ideas of Auguste Comte, Frederic Le Play and Elisée Reclus in order to reach a unified understanding of an urban development in a special context. This position would allow to represent the complexity of an inhabited environment through data.[15]

Thinking the Mundaneum

The only person that Otlet considered capable of the architectural realization of the Mundaneum was Le Corbusier, whom he approached for the first time in spring 1928. In one of the first letters he addressed the need to link “the idea and the building, in all its symbolic representation. […] Mundaneum opus maximum.” Aside from being a centre of documentation, information, science and education, the complex should link the Union of International Associations (UIA), which was founded by La Fontaine and Otlet in 1907, and the League of Nations. “A material and moral representation of The greatest Society of the nations (humanity);” an international city located on an extraterritorial area in Geneva.[16] Despite their different backgrounds, they easily understood each other, since they “did frequently use similar terms such as plan, analysis, classification, abstraction, standardization and synthesis, not only to bring conceptual order into their disciplines and knowledge organization, but also in human action.”[17] Moreover, the appearance of common terms in their most significant publications is striking. Such as spirit, mankind, elements, work, system and history, just to name a few. These circumstances led both Utopians to think the Mundaneum as a system, rather than a singular central type of building; it was meant to include as many resources in the development process as possible. Because the Mundaneum is “an idea, an institution, a method, a material corpus of works and collections, a building, a network,”[18] it had to be conceptualized as an “organic plan with the possibility to expand on different scales with the multiplication of each part.”[19] The possibility of expansion and an organic redistribution of elements adapted to new necessities and needs, is what guarantees the system efficiency, namely by constantly integrating more resources. By designing and standardizing forms of life up to the smallest element, modernism propagated a new form of living which would ensure the utmost efficiency. Otlet supported and encouraged Le Corbusier with his words: “The twentieth century is called upon to build a whole new civilization. From efficiency to efficiency, from rationalization to rationalization, it must so raise itself that it reaches total efficiency and rationalization. […] Architecture is one of the best bases not only of reconstruction (the deforming and skimpy name given to the whole of post-war activities) but of intellectual and social construction to which our era should dare to lay claim.”[20] Like the Wohnmaschine, in Corbusier’s famous housing project Unité d'habitation, the distribution of elements is shaped according to man's needs. The premise which underlies this notion is that man's needs and desires can be determined, normalized and standardized following geometrical models of objectivity.

“making transportation more efficient and lowering the cost of living, reducing energy usage and helping government operate more efficiently”[21]

Building the Mundaneum

In the first working phase, from March to September 1928, the plans for the Mundaneum seemed more a commissioned work than a collaboration. In the 3rd person singular, Otlet submitted descriptions and organizational schemes which would represent the institutional structures in a diagrammatic manner. In exchange, Le Corbusier drafted the architectural plans and detailed descriptions, which led to the publication N° 128 Mundaneum, printed by International Associations in Brussels.[22] Le Corbusier seemed a little less enthusiastic about the Mundaneum project than Otlet, mainly because of his scepticism towards the League of Nations, which he called a “misguided” and “pre-machinist creation.”[23] The rejection of his proposal for the Palace for the League of Nations in 1927, expressed with anger in a public announcement, might also play a role. However, the second phase, from September 1928 to August 1929, was marked by a strong friendship evidenced by the rise of the international debate after their first publications, letters starting with cher ami and their agreement to advance the project to the next level by including more stakeholders and developing the Cité mondiale. This led to the second publication by Paul Otlet, La Cité mondiale in February 1929, which unexpectedly traumatized the diplomatic environment in Geneva. Although both tried to organize personal meetings with key stakeholders, the project didn't find support for its realization, especially after Switzerland had withdrawn its offer of providing extraterritorial land for Cité mondiale. Instead, Le Corbusier focussed on his Ville Radieuse concept, which was presented at the 3rd CIAM meeting in Brussels in 1930.[24] He considered Cité mondiale as “a closed case”, and withdrew himself from the political environment by considering himself without any political color, “since the groups that gather around our ideas are, militaristic bourgeois, communists, monarchists, socialists, radicals, League of Nations and fascists. When all colors are mixed, only white is the result. That stands for prudence, neutrality, decantation and the human search for truth.”[25]

Governing the Mundaneum

Le Corbusier considered himself and his work “apolitical” or “above politics”.[26] Otlet, however, was more aware of the political force of this project. “Yet it is important to predict. To know in order to predict and to predict in order to control, was Comte's positive philosophy. Prediction doesn't cost a thing, was added by a master of contemporary urbanism (Le Corbusier).”[27] Lobbying for the Cité mondiale project, That prediction doesn't cost anything and is “preparing the ways for the coming years”, Le Corbusier wrote to Arthur Fontaine and Albert Thomas from the International Labor Organization that prediction is free and “preparing the ways for the coming years”.[28] Free because statistical data is always available, but he didn't seem to consider that prediction is a form of governing. A similar premise underlies the present domination of the smart city ideologies, where large amounts of data are used to predict for the sake of efficiency. Although most of the actors behind these ideas consider themselves apolitical, the governmental aspect is more than obvious. A form of control and government, which is not only biopolitical but rather epistemic. The data is not only used to standardize units for architecture, but also to determine categories of knowledge that restrict life to the normality of what can be classified. What becomes clear in this juxtaposition of Le Corbusier's and Paul Otlet's work is that the standardization of architecture goes hand in hand with an epistemic standardization because it limits what can be thought, experienced and lived to what is already there. This architecture has to be considered as an “epistemic object”, which exemplifies the cultural logic of its time.[29] By its presence it brings the abstract cultural logic underlying its conception into the everyday experience, and becomes with material, form and function an actor that performs an epistemic practice on its inhabitants and users. In this case: the conception that everything can be known, represented and (pre)determined through data.

- Jump up ↑ Paul Otlet, Monde: essai d'universalisme - Connaissance du Monde, Sentiment du Monde, Action organisee et Plan du Monde, (Bruxelles: Editiones Mundeum 1935): 448.

- Jump up ↑ Steve Lohr, Sidewalk Labs, a Start-Up Created by Google, Has Bold Aims to Improve City Living New, in York Times 11.06.15, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/11/technology/sidewalk-labs-a-start-up-created-by-google-has-bold-aims-to-improve-city-living.html?_r=0, quoted here is Dan Doctoroff, founder of Google Sidewalk Labs

- Jump up ↑ Dan Doctoroff, 10.06.2015, http://www.sidewalkinc.com/relevant

- Jump up ↑ Giuliano Gresleri and Dario Matteoni. La Città Mondiale: Andersen, Hébrard, Otlet, Le Corbusier. (Venezia: Marsilio, 1982): 128; See also: L. Van der Swaelmen, Préliminaires d'art civique (Leynde 1916): 164 – 299.

- Jump up ↑ Larry Page, Press release, 10.06.2015, http://www.sidewalkinc.com/

- Jump up ↑ Le Corbusier, “A Contemporary City” in The City of Tomorrow and its Planning, (New York: Dover Publications 1987): 164.

- Jump up ↑ ibid.: 105 & 126.

- Jump up ↑ ibid.: 108.

- Jump up ↑ Rayward, W Boyd, “Visions of Xanadu: Paul Otlet (1868–1944) and Hypertext” in Journal of the American Society for Information Science, (Volume 45, Issue 4, May 1994): 235.

- Jump up ↑ The french term dispositif or translated apparatus, refers to Michel Foucault's description of a merely strategic function, “a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions – in short, the said as much as the unsaid.” This distinction allows to go beyond the mere object, and rather deconstruct all elements involved in the production conditions and relate them to the distribution of power. See: Michel Foucault, “Confessions of the Flesh (1977) interview”, in Power/Knowledge Selected Interviews and Other Writings, Colin Gordon (Ed.), (New York: Pantheon Books 1980): 194 – 200.

- Jump up ↑ Bernd Frohmann, “The role of facts in Paul Otlet’s modernist project of documentation”, in European Modernism and the Information Society, Rayward, W.B. (Ed.), (London: Ashgate Publishers 2008): 79.

- Jump up ↑ “La régularisation de l’architecture et sa tendance à l’urbanisme total aident à mieux comprendre le livre et ses propres desiderata fonctionnels et intégraux.” See: Paul Otlet, Traité de documentation, (Bruxelles: Mundaneum, Palais Mondial, 1934): 329.

- Jump up ↑ “L'urbanisme est l'art d'aménager l'espace collectif en vue d'accroîte le bonheur humain général; l'urbanisation est le résulat de toute l'activité qu'une Société déploie pour arriver au but qu'elle se propose; l'expression matérielle (corporelle) de son organisation.” ibid.: 205.

- Jump up ↑ Thomas Pearce, Mettre des pierres autour des idées, Paul Otlet, de Cité Mondiale en de modernistische stedenbouw in de jaren 1930, (KU Leuven: PhD Thesis 2007): 39.

- Jump up ↑ Volker Welter, Biopolis Patrick Geddes and the City of Life. (Cambridge, Mass: MIT 2003).

- Jump up ↑ Letter from Paul Otlet to Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Brussels 2nd April 1928. See: Giuliano Gresleri and Dario Matteoni. La Città Mondiale: Andersen, Hébrard, Otlet, Le Corbusier. (Venezia: Marsilio, 1982): 221-223.

- Jump up ↑ W. Boyd Rayward (Ed.), European Modernism and the Information Society. (London: Ashgate Publishers 2008): 129.

- Jump up ↑ “Le Mundaneum est une Idée, une Institution, une Méthode, un Corps matériel de traveaux et collections, un Edifice, un Réseau.” See: Paul Otlet, Monde: essai d'universalisme - Connaissance du Monde, Sentiment du Monde, Action organisee et Plan du Monde, (Bruxelles: Editiones Mundeum 1935): 448.

- Jump up ↑ Giuliano Gresleri and Dario Matteoni. La Città Mondiale: Andersen, Hébrard, Otlet, Le Corbusier. (Venezia: Marsilio, 1982): 223.

- Jump up ↑ Le Corbusier, Radiant City, (New York: The Orion Press 1964): 27.

- Jump up ↑ http://www.sidewalkinc.com/

- Jump up ↑ Giuliano Gresleri and Dario Matteoni. La Città Mondiale: Andersen, Hébrard, Otlet, Le Corbusier. (Venezia: Marsilio, 1982): 128

- Jump up ↑ ibid.: 232.

- Jump up ↑ ibid.: 129.

- Jump up ↑ ibid.: 255.

- Jump up ↑ Eric Paul Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928-1960, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002): 20.

- Jump up ↑ “Savoir, pour prévoir afin de pouvoir, a été la lumineuse formule de Comte. Prévoir ne coûte rien, a ajouté un maître de l'urbanisme contemporain (Le Corbusier).” See: Paul Otlet, Monde: essai d'universalisme - Connaissance du Monde, Sentiment du Monde, Action organisee et Plan du Monde, (Bruxelles: Editiones Mundeum 1935): 407.

- Jump up ↑ Giuliano Gresleri and Dario Matteoni. La Città Mondiale: Andersen, Hébrard, Otlet, Le Corbusier. (Venezia: Marsilio, 1982): 241.

- Jump up ↑ Considering architecture as an object of knowledge formation, the term “epistemic object” by the German philosopher Günter Abel, helps bring forth the epistemic characteristic of architecture. Epistemic objects according to Abel are these, on which our knowledge and empiric curiosity are focused. They are objects that perform an active contribution to what can be thought and how it can be thought. Moreover because one cannot avoid architecture, it determines our boundaries (of thinking). See: Günter Abel, Epistemische Objekte – was sind sie und was macht sie so wertvoll?, in: Hingst, Kai-Michael; Liatsi, Maria (ed.), (Tübingen: Pragmata, 2008).