The radiated book

From Mondothèque

Mondothèque

Femke Snelting: Introduction

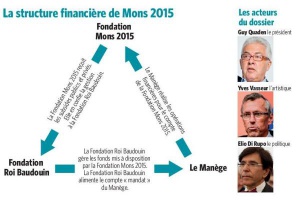

This Radiated Book started three years ago with an e-mail from the Mundaneum archive center in Mons. It announced that Elio di Rupo, then prime minister of Belgium, was about to sign a collaboration agreement between the archive center and Google. The newsletter cited an article in the French newspaper Le Monde that coined the Mundaneum as 'Google on paper' [1]. It was our first encounter with many variations on the same theme.

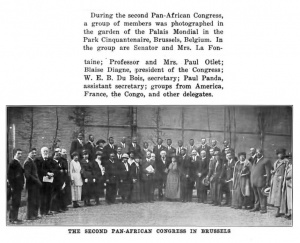

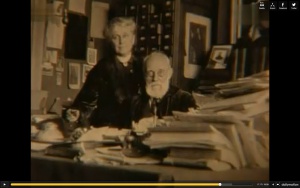

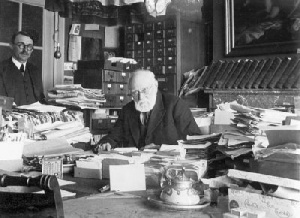

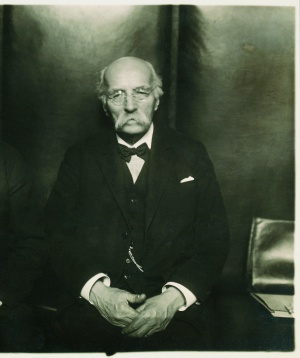

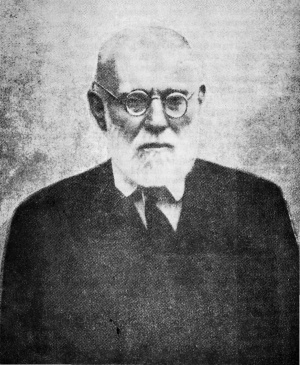

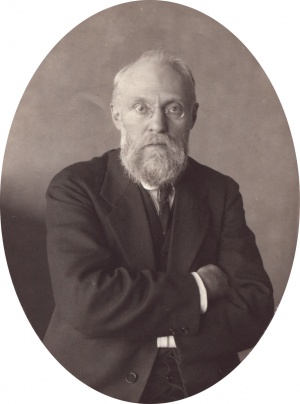

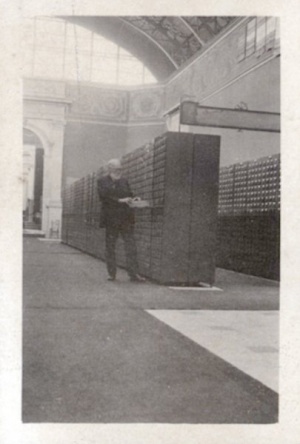

The former mining area around Mons is also where Google has installed its largest datacenter in Europe, a result of negotiations by the same Di Rupo[2]. Due to the re-branding of Paul Otlet as ‘founding father of the Internet’, Otlet's oeuvre finally started to receive international attention. Local politicians wanting to transform the industrial heartland into a home for The Internet Age seized the moment and made the Mundaneum a central node in their campaigns. Google — grateful for discovering its posthumous francophone roots — sent chief evangelist Vint Cerf to the Mundaneum. Meanwhile, the archive center allowed the company to publish hundreds of documents on the website of Google Cultural Institute.

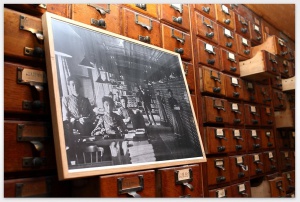

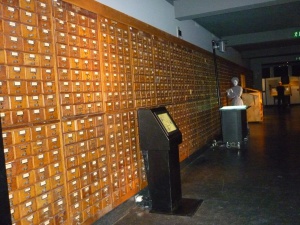

While the visual resemblance between a row of index drawers and a server park might not be a coincidence, it is something else to conflate the type of universalist knowledge project imagined by Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine with the enterprise of the search giant. The statement 'Google on paper' acted as a provocation, evoking other cases in other places where geographically situated histories are turned into advertising slogans, and cultural infrastructures pushed into the hands of global corporations.

An international band of artists, archivists and activists set out to unravel the many layers of this mesh. The direct comparison between the historical Mundaneum project and the mission of Alphabet Inc[3] speaks of manipulative simplification on multiple levels, but to de-tangle its implications was easier said than done. Some of us were drawn in by misrepresentations of the oeuvre of Otlet himself, others felt the need to give an account of its Brussels' roots, to re-insert the work of maintenance and caretaking into the his/story of founding fathers, or joined out of concern with the future of cultural institutions and libraries in digital times.

We installed a Semantic MediaWiki and named it after the Mondothèque, a device imagined by Paul Otlet in 1934. The wiki functioned as an online repository and frame of reference for the work that was developed through meetings, visits and presentations[4]. For Otlet, the Mondothèque was to be an 'intellectual machine': at the same time archive, link generator, writing desk, catalog and broadcast station. Thinking the museum, the library, the encyclopedia, and classificatory language as a complex and interdependent web of relations, Otlet imagined each element as a point of entry for the other. He stressed that responses to displays in a museum involved intellectual and social processes that where different from those involved in reading books in a library, but that one in a sense entailed the other. [5]. The dreamed capacity of his Mondothèque was to interface scales, perspectives and media at the intersection of all those different practices. For us, by transporting a historical device into the future, it figured as a kind of thinking machine, a place to analyse historical and social locations of the Mundaneum project, a platform to envision our persistent interventions together. The speculative figure of Mondothèque enabled us to begin to understand the situated formations of power around the project, and allowed us to think through possible forms of resistance. [6]

The wiki at http://mondotheque.be grew into a labyrinth of images, texts, maps and semantic links, tools and vocabularies. MediaWiki is a Free software infrastructure developed in the context of Wikipedia and comes with many assumptions about the kind of connections and practices that are desirable. We wanted to work with Semantic extensions specifically because we were interested in the way The Semantic Web[7] seemed to resemble Otlet's Universal Decimal Classification system. At many moments we felt ourselves going down rabbit-holes of universal completeness, endless categorisation and nauseas of scale. It made the work at times uncomfortable, messy and unruly, but it allowed us to do the work of unravelling in public, mixing political urgency with poetic experiments.

This Radiated Book was made because we wanted to create a moment, an incision into that radiating process that allowed us to invite many others a look at the interrelated materials without the need to provide a conclusive document. As a salute to Otlet's ever expanding Radiated Library, we decided to use the MediaWiki installation to write, edit and generate the publication which explains some of the welcome anomalies on the very pages of this book.

The four chapters that we propose each mix fact and fiction, text and image, document and catalogue. In this way, process and content are playing together and respond to the specific material entanglements that we encountered. Mondotheque, and as a consequence this Radiated book, is a multi-threaded, durational, multi-scalar adventure that in some way diffracts the all-encompassing ambition that the 19th century Utopia of Mundaneum stood for.

Embedded hierarchies addresses how classification systems, and the dream of their universal application actually operate. It brings together contributions that are concerned with knowledge infrastructures at different scales, from disobedient libraries, institutional practices of the digital archive, meta-data structures to indexing as a pathological condition.

Disambiguation dis-entangles some of the similarities that appear around the heritage of Paul Otlet. Through a close-reading of seemingly similar biographies, terms and vocabularies it re-locates ambiguity to other places.

Location, location, location is an account of geo-political layers at work. Following the itinerant archive of Mundaneum through the capital of Europe, we encounter local, national and global Utopias that in turn leave their imprint on the way the stories play out. From the hyperlocal to the global, this chapter traces patterns in the physical landscape.

Cross-readings consists of lists, image collections and other materials that make connections emerge between historical and contemporary readings, unearthing possible spiritual or mystical underpinnings of the Mundaneum, and transversal inclusions of the same elements in between different locations.

The point of modest operations such as Mondothèque is to build the collective courage to persist in demanding access to both the documents and the intellectual and technological infrastructures that interface and mediate them. Exactly because of the urgency of the situation, where the erosion of public institutions has become evident, and all forms of communication seem to feed into neo-liberal agendas eventually, we should resist simplifications and find the patience to build a relation to these histories in ways that makes sense. It is necessary to go beyond the current techno-determinist paradigm of knowledge production, and for this, imagination is indispensable.

The Book

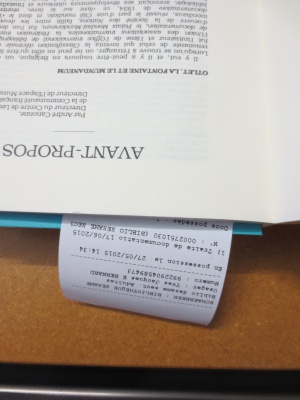

Alexia de Visscher: L'index du Traité

unité

211 3. Le Biblion.

Il y a désormais un terme générique (Biblion ou Bibliogramme ou Document) qui couvre à la fois toutes les espèces : volumes, brochures, revues, articles, cartes, diagrammes, photographies, estampes, brevets, statistiques, voire même disques phonographiques, verres ou films cinématographiques.Le « Biblion » sera pour nous l’unité intellectuelle et abstraite mais que l’on peut retrouver concrètement et réellement mais revêtue de modalités diverses.Dans le cosmos (ensemble des choses) le livre ou Document prend place parmi les choses corporelles (non incorporelles), artificielles (non naturelles), et ayant une utilité intellectuelle (non matérielle).Le Livre est un moyen de produire des utilités intellectuelles.212.4 Unité, multiples et sous-multiples

L’unité physique, matière du document, est marquée soit par la continuité matérielle de sa surface (ex. : la surface d’une lettre, d’un journal), soit par un lien matériel entre plusieurs surfaces (ex. : les feuilles reliées d’un livre), soit par un lien immatériel (ex. : les divers tomes d’un même ouvrage).L’unité intellectuelle est la pensée.Comme en toutes choses, on peut distinguer aussi dans le document : 1° l’unité ; 2° les parties ; 3° leur totalité ; 4° une pluralité d’unités ; 5° la totalité des unités.

On a vu précédemment ce qu’on peut considérer comme unité intellectuelle. Il y a des multiples et sous multiples des unités matérielles et intellectuelles.Toute chose considérée dans son ordre propre est placée au degré d’une échelle dont les deux extrémités sont le néant d’une part et la totalité d’autre part. Dans l’échelle de la série ainsi établie, on choisit plus ou moins arbitrairement une unité d’où l’on puisse procéder dans les deux directions montante et descendante. En ce qui concerne la Documentation, l’unité sera le livre, ses multiples seront les ensembles formés par le livre tels que les collections (bibliothèques) et ses sous-multiples seront des divisions telles que ses parties (chapitres, etc.).411.51 Unité (Complexité)

L’Unité consiste à concevoir comme un seul ensemble toute la Documentation et à tendre constamment à y ramener tout ce qui aurait tendance de s’en éloigner.Présentation

Comme il ne saurait s’agir d’une standardisation et d’une mécanisation totales du travail C’est à chacun à composer un « Manuel de Documentation » car celui-ci, s’il contient de nombreuses formules, n’a cependant en réalité rien d’un Formulaire.biblion

Le grec a donné le mot biblion, le latin le mot liber. On a fait de l'un Bibliographie, bibliologie, Bibliophilie, Bibliothèque; de l'autre Livre, Livresque, Libriairie[8]

111 Notion.

1. Livre (Biblion ou Document ou Gramme) est le terme conventionnel employé ici pour exprimer toute espèce de documents. Il comprend non seulement le livre proprement dit, manuscrit ou imprimé, mais les revues, les journaux, les écrits et reproductions graphiques de toute espèce, dessins, gravures, cartes, schémas, diagrammes, photographies, etc. Livre, éléments servant à indiquer ou reproduire une pensée envisagée sous n’importe quelle forme.

211 3. Le Biblion.

Il y a désormais un terme générique (Biblion ou Bibliogramme ou Document) qui couvre à la fois toutes les espèces : volumes, brochures, revues, articles, cartes, diagrammes, photographies, estampes, brevets, statistiques, voire même disques phonographiques, verres ou films cinématographiques.Le « Biblion » sera pour nous l’unité intellectuelle et abstraite mais que l’on peut retrouver concrètement et réellement mais revêtue de modalités diverses.Dans le cosmos (ensemble des choses) le livre ou Document prend place parmi les choses corporelles (non incorporelles), artificielles (non naturelles), et ayant une utilité intellectuelle (non matérielle).Le Livre est un moyen de produire des utilités intellectuelles.

411.1 Les documents.

2° L’Image (Icone). Elle reproduit la réalité. On distingue la reproduction directe de la réalité. Elle s’opère par l’un des procédés suivants : tableau, aquarelle (en couleurs) isolé ou mobile ou fixe (fresque), plafond, encadrement dans une paroi dans un objet, dessin (noir ou couleur), gravure, photographie, sculpture.Les écrits (Biblion). On distingue qu’ils sont ou relatifs directement à la réalité ou bien relatifs à une image, et alors ils sont : a) ou relatifs à une reproduction de la réalité, soit tableau, dessin, gravure, photographie, sculpture ; b) ou relatifs à une reproduction d’une reproduction faite à son tour par tableau, dessin, gravure, photographie ou sculpture.1. Réalité.2. Reproduction de la réalité.

3. Écrit sur une reproduction de la réalité.1. Choses elles-mêmes.

2. La mention de chose dans la classification.

3. Le catalogue général inventoriant les choses en elles-mêmes ou appartenant à des collections déterminées.

4. Le catalogue (général ou particulier) de documents relatifs aux choses. 1. Auteur de l’original.

2. Auteur de la reproduction.

111 Notion.

1. Livre (Biblion ou Document ou Gramme) est le terme conventionnel employé ici pour exprimer toute espèce de documents. Il comprend non seulement le livre proprement dit, manuscrit ou imprimé, mais les revues, les journaux, les écrits et reproductions graphiques de toute espèce, dessins, gravures, cartes, schémas, diagrammes, photographies, etc. Livre, éléments servant à indiquer ou reproduire une pensée envisagée sous n’importe quelle forme.211 3. Le Biblion.

Il y a désormais un terme générique (Biblion ou Bibliogramme ou Document) qui couvre à la fois toutes les espèces : volumes, brochures, revues, articles, cartes, diagrammes, photographies, estampes, brevets, statistiques, voire même disques phonographiques, verres ou films cinématographiques.Le « Biblion » sera pour nous l’unité intellectuelle et abstraite mais que l’on peut retrouver concrètement et réellement mais revêtue de modalités diverses.Dans le cosmos (ensemble des choses) le livre ou Document prend place parmi les choses corporelles (non incorporelles), artificielles (non naturelles), et ayant une utilité intellectuelle (non matérielle).Le Livre est un moyen de produire des utilités intellectuelles.411.1 Les documents.

2° L’Image (Icone). Elle reproduit la réalité. On distingue la reproduction directe de la réalité. Elle s’opère par l’un des procédés suivants : tableau, aquarelle (en couleurs) isolé ou mobile ou fixe (fresque), plafond, encadrement dans une paroi dans un objet, dessin (noir ou couleur), gravure, photographie, sculpture.Les écrits (Biblion). On distingue qu’ils sont ou relatifs directement à la réalité ou bien relatifs à une image, et alors ils sont : a) ou relatifs à une reproduction de la réalité, soit tableau, dessin, gravure, photographie, sculpture ; b) ou relatifs à une reproduction d’une reproduction faite à son tour par tableau, dessin, gravure, photographie ou sculpture.1. Réalité.2. Reproduction de la réalité.

3. Écrit sur une reproduction de la réalité.1. Choses elles-mêmes.

2. La mention de chose dans la classification.

3. Le catalogue général inventoriant les choses en elles-mêmes ou appartenant à des collections déterminées.

4. Le catalogue (général ou particulier) de documents relatifs aux choses. 1. Auteur de l’original.

2. Auteur de la reproduction.

coquille

222.11 Notion.

La disposition donnée à l’écriture sur le papier a quelque chose de fondamental. En principe on peut écrire normalement de gauche à droite et d’en dessus en dessous, mais l’inverse est possible. De droite à gauche, de bas en haut, on peut écrire et commencer par la première page à partir de l’extérieur ou par la page du milieu.En principe, l’écriture est linéaire, car elle suit l’énonciation des sons qui se succèdent dans le temps. La ligne a donc pris trois directions fondamentales : horizontale, verticale et retour. (Boustropheron).L’écriture pourrait-elle être transformée de simplement linéaire en surface et y aurait-il quelque parti à tirer d’une écriture plurilinéaire à la manière des partitions musicales ou des notations chimiques ? Sur des lignes superposées, ayant même direction, ou sur des lignes prenant d’un point central des directions diverses seraient écrits les développements d’un exposé qui se succèdent aujourd’hui linéairement.

Errata

ANNEXE ERRATA : ( Page omise ).

373 bis.222.11 Notion.

La disposition donnée à l’écriture sur le papier a quelque chose de fondamental. En principe on peut écrire normalement de gauche à droite et d’en dessus en dessous, mais l’inverse est possible. De droite à gauche, de bas en haut, on peut écrire et commencer par la première page à partir de l’extérieur ou par la page du milieu.En principe, l’écriture est linéaire, car elle suit l’énonciation des sons qui se succèdent dans le temps. La ligne a donc pris trois directions fondamentales : horizontale, verticale et retour. (Boustropheron).L’écriture pourrait-elle être transformée de simplement linéaire en surface et y aurait-il quelque parti à tirer d’une écriture plurilinéaire à la manière des partitions musicales ou des notations chimiques ? Sur des lignes superposées, ayant même direction, ou sur des lignes prenant d’un point central des directions diverses seraient écrits les développements d’un exposé qui se succèdent aujourd’hui linéairement.Errata

ANNEXE ERRATA : ( Page omise ).

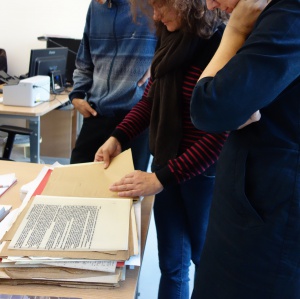

373 bis.Tomislav Medak, Marcell Mars & Sean Dockray: A curriculum in amateur librarianship

Tomislav Medak & Marcell Mars (Public Library project)

Public library, a political genealogy

Public libraries have historically achieved as an institutional space of exemption from the commodification and privatization of knowledge. A space where works of literature and science are housed and made accessible for the education of every member of society regardless of their social or economic status. If, as a liberal narrative has it, education is a prerequisite for full participation in a body politic, it is in this narrow institutional space that citizenship finds an important material base for its universal realization.

The library as an institution of public access and popular literacy, however, did not develop before a series of transformations and social upheavals unfolded in the course of 18th and 19th century. These developments brought about a flood of books and political demands pushing the library to become embedded in an egalitarian and democratizing political horizon. The historic backdrop for these developments was the rapid ascendancy of the book as a mass commodity and the growing importance of the reading culture in the aftermath of the invention of the movable type print. Having emerged almost in parallel with capitalism, by the early 18th century the trade in books was rapidly expanding. While in the 15th century the libraries around the monasteries, courts and universities of Western Europe contained no more than 5 million manuscripts, the output of printing presses in the 18th century alone exploded to formidable 700 million volumes.[9] And while this provided a vector for the emergence of a bourgeois reading public and an unprecedented expansion of modern science, the culture of reading and Enlightenment remained largely a privilege of the few.

Two social upheavals would start to change that. On 2 November 1789 the French revolutionary National Assembly passed a decision to seize all library holdings from the Church and aristocracy. Millions of volumes were transferred to the Bibliothèque Nationale and local libraries across France. At the same time capitalism was on the rise, particularly in England. It massively displaced the impoverished rural population into growing urban centres, propelled the development of industrial production and, by the mid-19th century, introduced the steam-powered rotary press into the commercial production of books.Template loop detected: Amateur Librarian - A Course in Critical Pedagogy

Puisqu'il était de plus en plus facile de produire des livres en masse, les bibliothèques privées payantes, au service des catégories privilégiées de la société, ont commencé à se répandre. Ce phénomène a mis en relief la question de la classe dans la demande naissante pour un accès public aux livres.

After the failed attempt to introduce universal suffrage and end the system of political representation based on property entitlements through the Reform Act of 1832, the English Chartist movement started to open reading rooms and cooperative lending libraries that would quickly become a popular hotbed of social exchange between the lower classes. In the aftermath of the revolutionary upheavals of 1848, the fearful ruling classes finally consented to the demand for tax-financed public libraries, hoping that the access to literature and edification would after all help educate skilled workers that were increasingly in demand and ultimately hegemonize the working class for the benefits of capitalism's culture of self-interest and competition.[10]

Really useful knowledge

It's no surprise that the Chartists, reeling from a political defeat, had started to open reading rooms and cooperative lending libraries. The education provided to the proletariat and the poor by the ruling classes of that time consisted, indeed, either of a pious moral edification serving political pacification or of an inculcation of skills and knowledge useful to the factory owner. Even the seemingly noble efforts of the Society for the Diffusion of the Useful Knowledge, a Whig organization aimed at bringing high-brow learning to the middle and working classes in the form of simplified and inexpensive publications, were aimed at dulling the edge of radicalism of popular movements.[12]

These efforts to pacify the downtrodden masses pushed them to seek ways of self-organized education that would provide them with literacy and really useful knowledge – not applied, but critical knowledge that would allow them to see through their own political and economic subjection, develop radical politics and innovate shadow social institutions of their own. The radical education, reliant on meagre resources and time of the working class, developed in the informal setting of household, neighbourhood and workplace, but also through radical press and communal reading and discussion groups.[13]

The demand for really useful knowledge encompassed a critique of “all forms of ‘provided’ education” and of the liberal conception “that ‘national education’ was a necessary condition for the granting of universal suffrage.” Development of radical “curricula and pedagogies” formed a part of the arsenal of “political strategy as a means of changing the world.”[14]

Critical pedagogy

This is the context of the emergence of the public library. A historical compromise between a push for radical pedagogy and a response to dull its edge. And yet with the age of digitization, where one would think that the opportunities for access to knowledge have expanded immensely, public libraries find themselves increasingly limited in their ability to acquire and lend both digital and paper editions. It is a sign of our radically unequal times that the political emancipation finds itself on a defensive fighting again for this material base of pedagogy against the rising forces of privatization. Not only has mass education become accessible only under the condition of high fees, student debt and adjunct peonage, but the useful knowledge that the labour market and reproduction of the neoliberal capitalism demands has become the one and only rationale for education.

No wonder that over the last 6-7 years we have seen self-education, shadow libraries and amateur librarians emerge again to counteract the contraction of spaces of exemption that have been shrunk by austerity and commodity.

The project Public Library was initiated with the counteraction in mind. To help everyone learn to use simple tools to be able to act as an Amateur Librarian – to digitize, to collect, to share, to preserve books and articles that were unaffordable, unavailable, undesirable in the troubled corners of the Earth we hail from.

Amateur Librarian played an important role in the narrative of Public Library. And it seems it was successful. People easily join the project by 'becoming' a librarian using Calibre[15] and [let’s share books].[16] Other aspects of the Public Library narrative add a political articulation to that simple yet disobedient act. Public Library detects an institutional crisis in education, an economic deadlock of austerity and a domination of commodity logic in the form of copyright. It conjures up the amateur librarians’ practice of sharing books/catalogues as a relevant challenge against the convergence of that crisis, deadlock and copyright regime.

To understand the political and technological assumptions and further develop the strategies that lie behind the counteractions of amateur librarians, we propose a curriculum that is indebted to a tradition of critical pedagogy. Critical pedagogy is a productive and theoretical practice rejecting an understanding of educational process that reduces it to a technique of imparting knowledge and a neutral mode of knowledge acquisition. Rather, it sees the pedagogy as a broader “struggle over knowledge, desire, values, social relations, and, most important, modes of political agency”, “drawing attention to questions regarding who has control over the conditions for the production of knowledge.”[17]

Actuellement, aucune industrie ne montre plus d'asymétries au niveau du contrôle des conditions de production de la connaissance que celle de la publication académique. Refuser l'accès à des publications académiques excessivement chères pour beaucoup d'universités, en particulier dans l'hémisphère sud, contraste ostensiblement avec les profits énormes qu'un petit nombre d'éditeurs commerciaux tirent du travail bénévole de scientifiques qui écrivent, révisent et éditent des contributions et avec les prix exorbitants des souscriptions que les bibliothèques institutionnelles doivent payer.

FS: Hoe gaan jullie om met boeken en publicaties die al vanaf het begin digitaal zijn? DM: We kopen e-books en e-tijdschriften en maken die beschikbaar voor onderzoekers. Maar dat zijn hele andere omgevingen, omdat die content niet fysiek binnen onze muren komt. We kopen toegang tot servers van uitgevers of de aggregator. Die content komt nooit bij ons, die blijft op hun machines staan. We kunnen daar dus eigenlijk niet zoveel mee doen, behalve verwijzen en zorgen dat het evengoed vindbaar is als de print.

A curriculum

Public library is:

- free access to books for every member of society,

- library catalogue,

- librarian.

Template loop detected: Amateur Librarian - A Course in Critical Pedagogy

Tout en restant schématique en allant de la pratique immédiate, à la stratégie, la tactique et au registre réflectif de la connaissance, il existe des personnes et pratiques - non citées ici - desquelles nous imaginons pouvoir apprendre.

The first iteration of this curriculum could be either a summer academy rostered with our all-star team of librarians, designers, researchers and teachers, or a small workshop with a small group of students delving deeper into one particular aspect of the curriculum. In short it is an open curriculum: both open to educational process and contributions by others. We welcome comments, derivations and additions.

MODULE 1: Workflows

- from book to e-book

- digitizing a book on a book scanner

- removing DRM and converting e-book formats

- from clutter to catalogue

- managing an e-book library with Calibre

- finding e-books and articles on online libraries

- from reference to bibliography

- annotating in an e-book reader device or application

- creating a scholarly bibliography in Zotero

- from block device to network device

- sharing your e-book library on a local network to a reading device

- sharing your e-book library on the internet with [let’s share books]

- from private to public IP space

- using [let’s share books] & library.memoryoftheworld.org

- using logan & jessica

- using Science Hub

- using Tor

MODULE 2: Politics/tactics

- from developmental subordination to subaltern disobedience

- uneven development & political strategies

- strategies of the developed v strategies of the underdeveloped : open access v piracy

- from property to commons

- from property to commons

- copyright, scientific publishing, open access

- shadow libraries, piracy, custodians.online

- from collection to collective action

- critical pedagogy & education

- archive, activation & collective action

MODULE 3: Abstractions in action

- from linear to computational

- library & epistemology: catalogue, search, discovery, reference

- print book v e-book: page, margin, spine

- from central to distributed

- deep librarianship & amateur librarians

- network infrastructure(s)/topologies (ruling class studies)

- from factual to fantastic

- universe as library as universe

Reading List

- Mars, Marcell; Vladimir, Klemo. Download & How to: Calibre & [let’s share books]. Memory of the World (2014) https://www.memoryoftheworld.org/blog/2014/10/28/calibre-lets-share-books/

- Buringh, Eltjo; Van Zanden, Jan Luiten. Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries. The Journal of Economic History (2009) http://journals.cambridge.org/article_S0022050709000837

- Mattern, Shannon. Library as Infrastructure. Places Journal (2014) https://placesjournal.org/article/library-as-infrastructure/

- Antonić, Voja. Our beloved bookscanner. Memory of the World (2012) https://www.memoryoftheworld.org/blog/2012/10/28/our-beloved-bookscanner-2/

- Medak, Tomislav; Sekulić, Dubravka; Mertens, An. How to: Bookscanning. Memory of the World (2014) https://www.memoryoftheworld.org/blog/2014/12/08/how-to-bookscanning/

- Barok, Dušan. Talks/Public Library. Monoskop (2015) http://monoskop.org/Talks/Public_Library

- Custodians.online. In Solidarity with Library Genesis and Science Hub (2015) http://custodians.online

- Battles, Matthew. Library: An Unquiet History Random House (2014)

- Harris, Michael H. History of Libraries of the Western World. Scarecrow Press (1999)

- MayDay Rooms. Activation (2015) http://maydayrooms.org/activation/

- Krajewski, Markus. Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. MIT Press (2011) https://library.memoryoftheworld.org/b/PaRC3gldHrZ3MuNPXyrh1hM1meyyaqvhaWl-HTvr53NRjJ2k

For updates: https://www.zotero.org/groups/amateur_librarian_-_a_course_in_critical_pedagogy_reading_list

Dries Moreels: 7 years of Google Books (interview)

The Drawer

Sînziana Păltineanu: An experimental transcript

Note: The editor has had the good fortune of finding a whole box of handwritten index cards and various folded papers (from printed screenshots to boarding passes) in the storage space of an institute. Upon closer investigation, it has become evident that the mixed contents of the box make up one single document. Difficult to decipher due to messy handwriting, the manuscript poses further challenges to the reader because its fragments lack a pre-established order. Simply uploading high-quality facsimile images of the box contents here would not solve the problems of legibility and coherence. As an intermediary solution, the editor has opted to introduce below a selection of scanned images and transcribed text from the found box. The transcript is intended to be read as a document sample, as well as an attempt at manuscript reconstruction, following the original in the author's hand as closely as possible: pencilled in words in the otherwise black ink text are transcribed in brackets, whereas curly braces signal erasures, peculiar marks or illegible parts on the index cards. Despite shifts in handwriting styles, whereby letters sometimes appear extremely rushed and distorted in multiple idiosyncratic ways, the experts consulted unanimously declared that the manuscript was most likely authored by one and the same person. To date, the author remains unknown.

Stéphanie Manfroid: Memory of the world (interview)

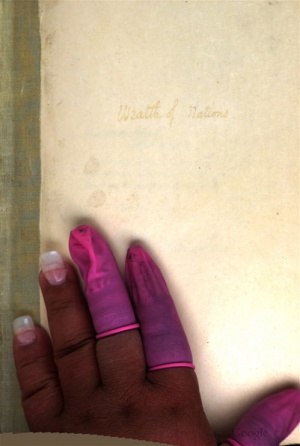

Alexia de Visscher: À la recherche de l'UDC

The Universal Decimal Classification system that Paul Otlet developed with Henri Lafontaine from 1905 onwards, is still in use. Here we document our explorations of the multi-directional system, thinking through it's relevance and relations to technologies of today.

The Desk

Matthew Fuller: The professor and the siren

A fictional text based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedus's story The professor and the siren, where the ineffable feeling of fluid efficiency given by the correct apportionment of equipment and index cards, functions as the muse or siren.

Robert Ochshorn: Deep skimming, blind reading

Dusan Barok: Knowing on the fly

Michael Murtaugh: a bag but is language nothing of words (language is nothing but a bag of words)

(language is nothing but a bag of words)

Bag of words

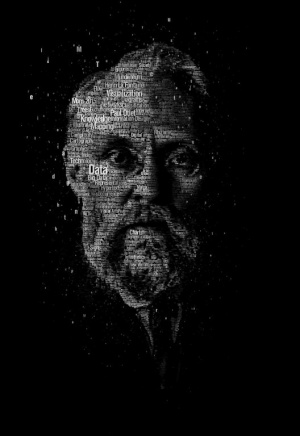

In information retrieval and other so-called machine-reading applications (such as text indexing for web search engines) the term "bag of words" is used to underscore how in the course of processing a text the original order of the words in sentence form is stripped away. The resulting representation is then a collection of each unique word used in the text, typically weighted by the number of times the word occurs.

Bag of words, also known as word histograms or weighted term vectors, are a standard part of the data engineer's toolkit. But why such a drastic transformation? The utility of "bag of words" is in how it makes text amenable to code, first in that it's very straightforward to implement the translation from a text document to a bag of words representation. More significantly, this transformation then opens up a wide collection of tools and techniques for further transformation and analysis purposes. For instance, a number of libraries available in the booming field of "data sciences" work with "high dimension" vectors; bag of words is a way to transform a written document into a mathematical vector where each "dimension" corresponds to the (relative) quantity of each unique word. While physically unimaginable and abstract (imagine each of Shakespeare's works as points in a 14 million dimensional space), from a formal mathematical perspective, it's quite a comfortable idea, and many complementary techniques (such as principle component analysis) exist to reduce the resulting complexity.

What's striking about a bag of words representation, given is centrality in so many text retrieval application is its irreversibility. Given a bag of words representation of a text and faced with the task of producing the original text would require in essence the "brain" of a writer to recompose sentences, working with the patience of a devoted cryptogram puzzler to draw from the precise stock of available words. While "bag of words" might well serve as a cautionary reminder to programmers of the essential violence perpetrated to a text and a call to critically question the efficacy of methods based on subsequent transformations, the expressions use seems in practice more like a badge of pride or a schoolyard taunt that would go: Hey language: you're nothing but a big BAG-OF-WORDS. Following this spirit of the term, "bag of words" celebrates a perfunctory step of "breaking" a text into a purer form amenable to computation, to stripping language of its silly redundant repetitions and foolishly contrived stylistic phrasings to reveal a purer inner essence.

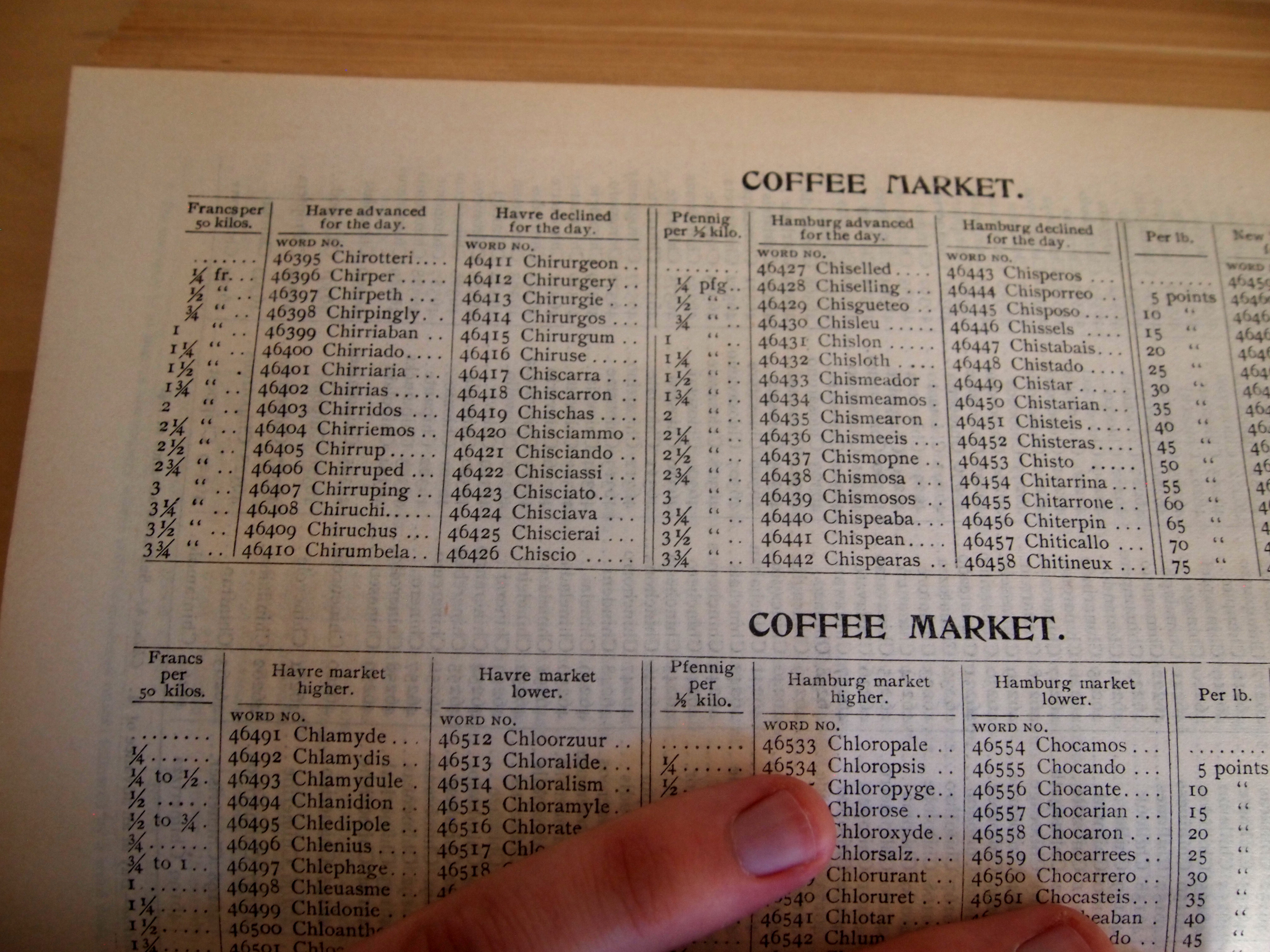

Book of words

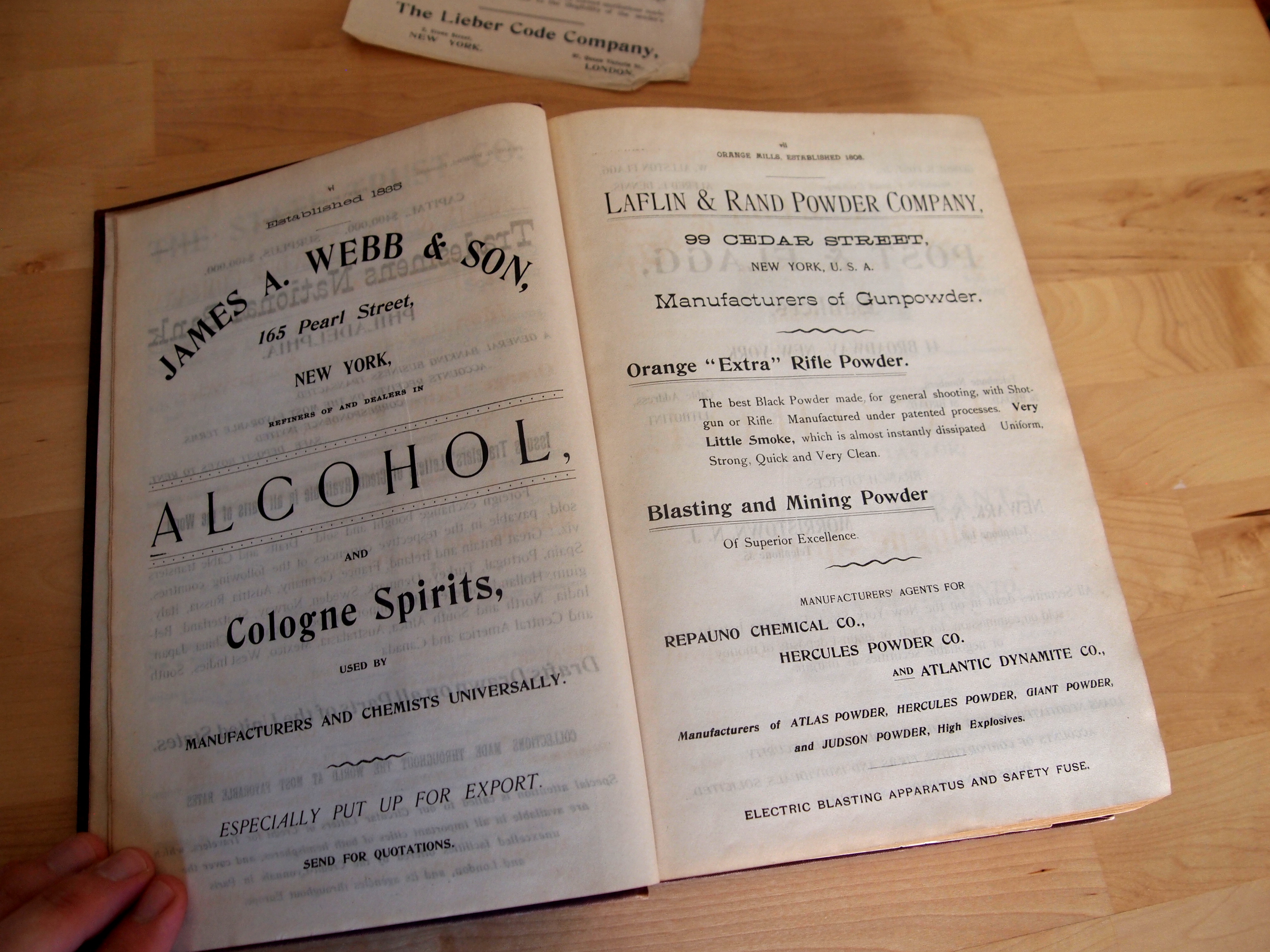

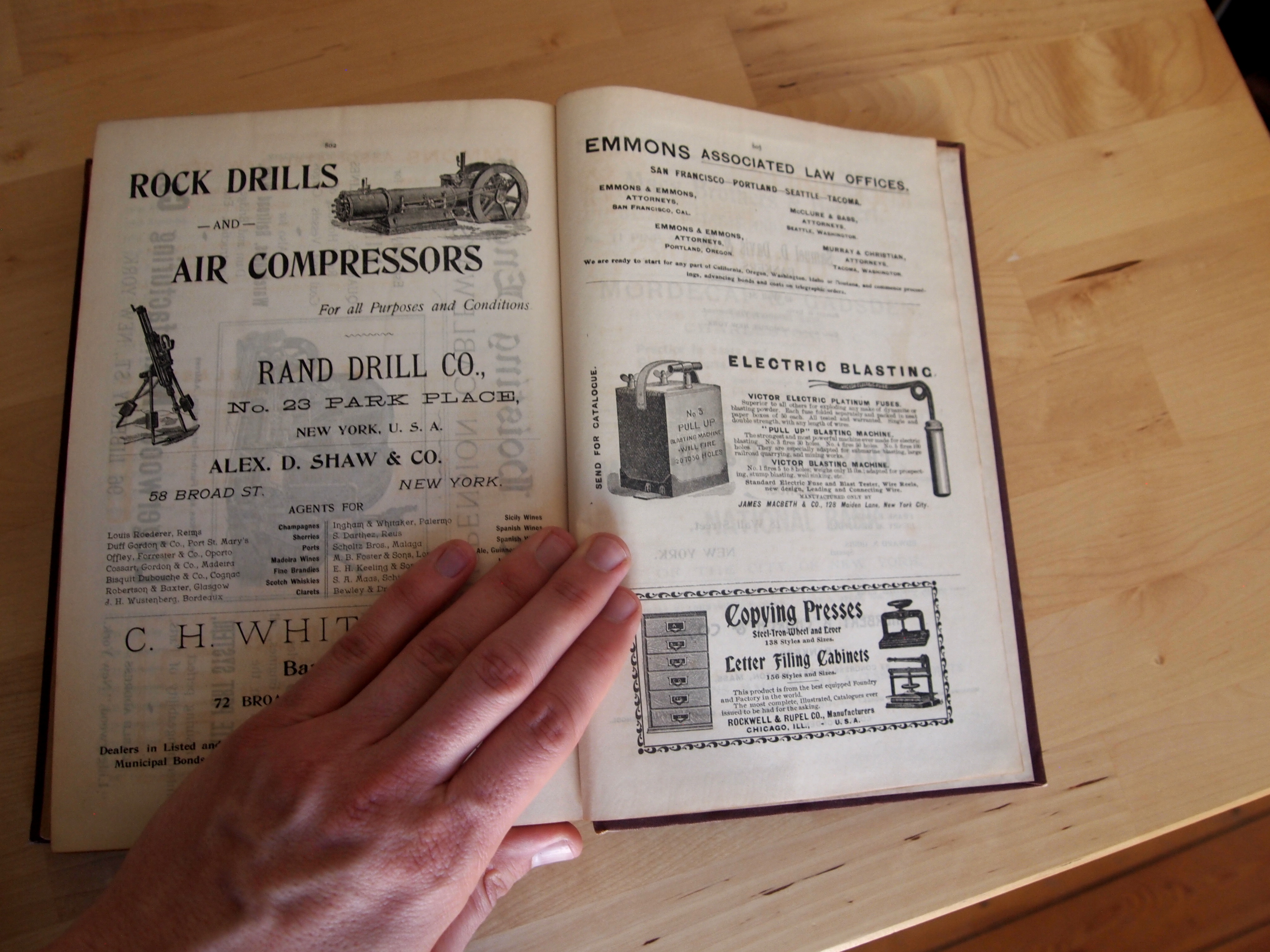

Lieber's Standard Telegraphic Code, first published in 1896 and republished in various updated editions through the early 1900s, is an example of one of several competing systems of telegraph code books. The idea was for both senders and receivers of telegraph messages to use the books to translate their messages into a sequence of code words which can then be sent for less money as telegraph messages were paid by the word. In the front of the book, a list of examples gives a sampling of how messages like: "Have bought for your account 400 bales of cotton, March delivery, at 8.34" can be conveyed by a telegram with the message "Ciotola, Delaboravi". In each case the reduction of number of transmitted words is highlighted to underscore the efficacy of the method. Like a dictionary or thesaurus, the book is primarily organized around key words, such as act, advice, affairs, bags, bail, and bales, under which exhaustive lists of useful phrases involving the corresponding word are provided in the main pages of the volume. [18]

[...] my focus in this chapter is on the inscription technology that grew parasitically alongside the monopolistic pricing strategies of telegraph companies: telegraph code books. Constructed under the bywords “economy,” “secrecy,” and “simplicity,” telegraph code books matched phrases and words with code letters or numbers. The idea was to use a single code word instead of an entire phrase, thus saving money by serving as an information compression technology. Generally economy won out over secrecy, but in specialized cases, secrecy was also important.[19]

In Katherine Hayles' chapter devoted to telegraph code books she observes how:

The interaction between code and language shows a steady movement away from a human-centric view of code toward a machine-centric view, thus anticipating the development of full-fledged machine codes with the digital computer. [20]

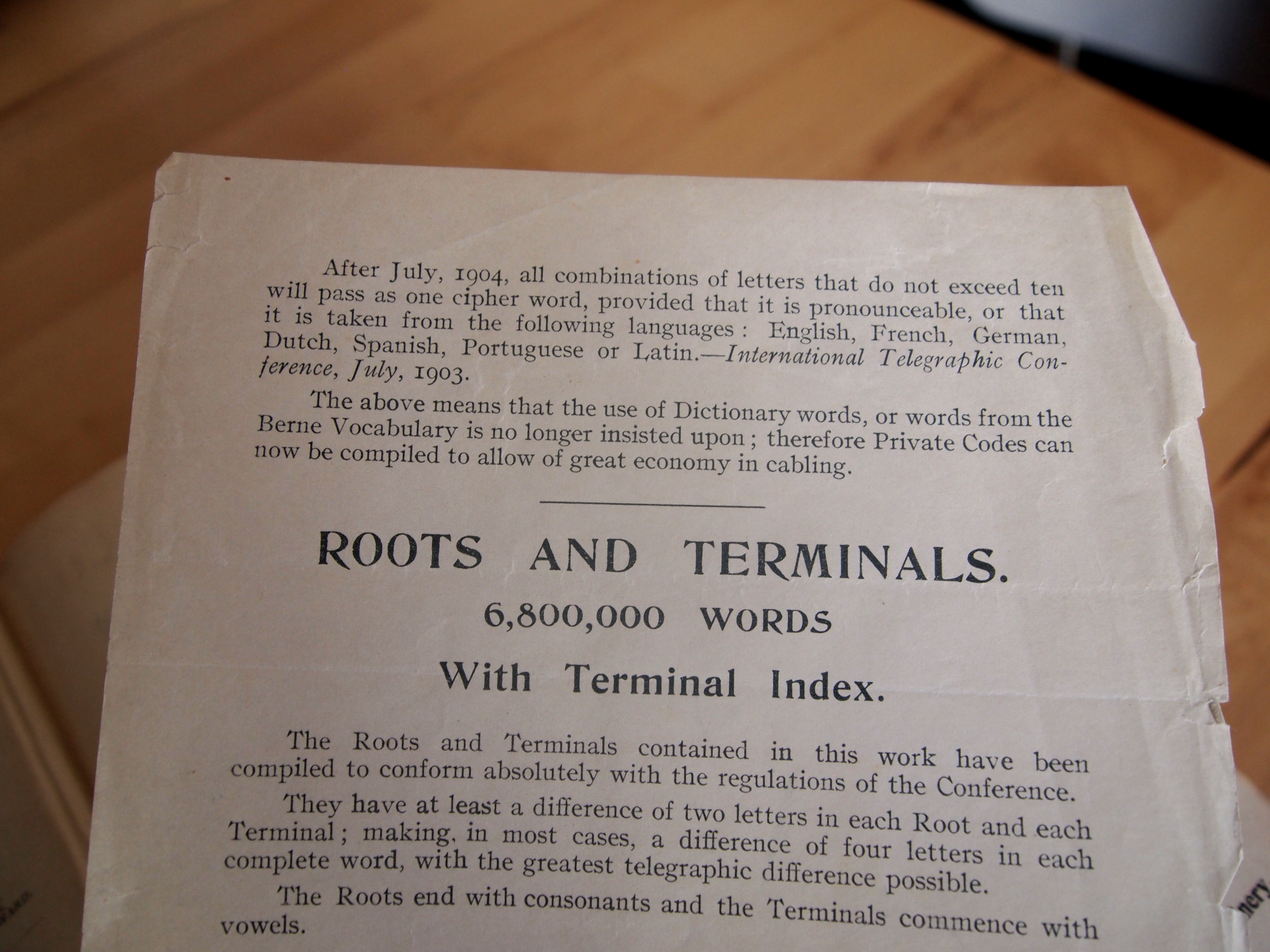

After July, 1904, all combinations of letters that do not exceed ten will pass as one cipher word, provided that it is pronounceable, or that it is taken from the following languages: English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese or Latin -- International Telegraphic Conference, July 1903 [21]

Conforming to international conventions regulating telegraph communication at that time, the stipulation that code words be actual words drawn from a variety of European languages (many of Lieber's code words are indeed arbitrary Dutch, German, and Spanish words) underscores this particular moment of transition as reference to the human body in the form of "pronounceable" speech from representative languages begins to yield to the inherent potential for arbitrariness in digital representation.

What telegraph code books do is remind us of is the relation of language in general to economy. Whether they may be economies of memory, attention, costs paid to a telecommunicatons company, or in terms of computer processing time or storage space, encoding language or knowledge in any form of writing is a form of shorthand and always involves an interplay with what one expects to perform or "get out" of the resulting encoding.

Along with the invention of telegraphic codes comes a paradox that John Guillory has noted: code can be used both to clarify and occlude. Among the sedimented structures in the technological unconscious is the dream of a universal language. Uniting the world in networks of communication that flashed faster than ever before, telegraphy was particularly suited to the idea that intercultural communication could become almost effortless. In this utopian vision, the effects of continuous reciprocal causality expand to global proportions capable of radically transforming the conditions of human life. That these dreams were never realized seems, in retrospect, inevitable. [22]

Far from providing a universal system of encoding messages in the English language, Lieber's code is quite clearly designed for the particular needs and conditions of its use. In addition to the phrases ordered by keywords, the book includes a number of tables of terms for specialized use. One table lists a set of words used to describe all possible permutations of numeric grades of coffee (Choliam = 3,4, Choliambos = 3,4,5, Choliba = 4,5, etc.); another table lists pairs of code words to express the respective daily rise or fall of the price of coffee at the port of Le Havre in increments of a quarter of a Franc per 50 kilos ("Chirriado = prices have advanced 1 1/4 francs"). From an archaeological perspective, the Lieber's code book reveals a cross section of the needs and desires of early 20th century business communication between the United States and its trading partners.

The advertisements lining the Liebers Code book further situate its use and that of commercial telegraphy. Among the many advertisements for banking and law services, office equipment, and alcohol are several ads for gun powder and explosives, drilling equipment and metallurgic services all with specific applications to mining. Extending telegraphy's formative role for ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship communication for reasons of safety, commercial telegraphy extended this network of communication to include those parties coordinating the "raw materials" being mined, grown, or otherwise extracted from overseas sources and shipped back for sale.

"Raw data now!"

Étant donné que les nouvelles formes modernistes et l'utilisation de matériaux propageaient l'abondance d'éléments décoratifs, Paul Otlet croyait en la possibilité du langage comme modèle de « données brutes », le réduisant aux informations essentielles et aux faits sans ambiguïté, tout en se débarrassant de tous les éléments inefficaces et subjectifs.

As new modernist forms and use of materials propagated the abundance of decorative elements, Otlet believed in the possibility of language as a model of 'raw data', reducing it to essential information and unambiguous facts, while removing all inefficient assets of ambiguity or subjectivity.

Tim Berners-Lee: [...] Make a beautiful website, but first give us the unadulterated data, we want the data. We want unadulterated data. OK, we have to ask for raw data now. And I'm going to ask you to practice that, OK? Can you say "raw"?

Audience: Raw.

Tim Berners-Lee: Can you say "data"?

Audience: Data.

TBL: Can you say "now"?

Audience: Now!

TBL: Alright, "raw data now"!

[...]

So, we're at the stage now where we have to do this -- the people who think it's a great idea. And all the people -- and I think there's a lot of people at TED who do things because -- even though there's not an immediate return on the investment because it will only really pay off when everybody else has done it -- they'll do it because they're the sort of person who just does things which would be good if everybody else did them. OK, so it's called linked data. I want you to make it. I want you to demand it. [23]

Un/Structured

As graduate students at Stanford, Sergey Brin and Lawrence (Larry) Page had an early interest in producing "structured data" from the "unstructured" web. [24]

The World Wide Web provides a vast source of information of almost all types, ranging from DNA databases to resumes to lists of favorite restaurants. However, this information is often scattered among many web servers and hosts, using many different formats. If these chunks of information could be extracted from the World Wide Web and integrated into a structured form, they would form an unprecedented source of information. It would include the largest international directory of people, the largest and most diverse databases of products, the greatest bibliography of academic works, and many other useful resources. [...]

2.1 The Problem

Here we define our problem more formally:

Let D be a large database of unstructured information such as the World Wide Web [...] [25]

In a paper titled Dynamic Data Mining Brin and Page situate their research looking for rules (statistical correlations) between words used in web pages. The "baskets" they mention stem from the origins of "market basket" techniques developed to find correlations between the items recorded in the purchase receipts of supermarket customers. In their case, they deal with web pages rather than shopping baskets, and words instead of purchases. In transitioning to the much larger scale of the web, they describe the usefulness of their research in terms of its computational economy, that is the ability to tackle the scale of the web and still perform using contemporary computing power completing its task in a reasonably short amount of time.

A traditional algorithm could not compute the large itemsets in the lifetime of the universe. [...] Yet many data sets are difficult to mine because they have many frequently occurring items, complex relationships between the items, and a large number of items per basket. In this paper we experiment with word usage in documents on the World Wide Web (see Section 4.2 for details about this data set). This data set is fundamentally different from a supermarket data set. Each document has roughly 150 distinct words on average, as compared to roughly 10 items for cash register transactions. We restrict ourselves to a subset of about 24 million documents from the web. This set of documents contains over 14 million distinct words, with tens of thousands of them occurring above a reasonable support threshold. Very many sets of these words are highly correlated and occur often. [26]

Un/Ordered

In programming, I've encountered a recurring "problem" that's quite symptomatic. It goes something like this: you (the programmer) have managed to cobble out a lovely "content management system" (either from scratch, or using any number of helpful frameworks) where your user can enter some "items" into a database, for instance to store bookmarks. After this ordered items are automatically presented in list form (say on a web page). The author: It's great, except... could this bookmark come before that one? The problem stems from the fact that the database ordering (a core functionality provided by any database) somehow applies a sorting logic that's almost but not quite right. A typical example is the sorting of names where details (where to place a name that starts with a Norwegian "Ø" for instance), are language-specific, and when a mixture of languages occurs, no single ordering is necessarily "correct". The (often) exascerbated programmer might hastily add an additional database field so that each item can also have an "order" (perhaps in the form of a date or some other kind of (alpha)numerical "sorting" value) to be used to correctly order the resulting list. Now the author has a means, awkward and indirect but workable, to control the order of the presented data on the start page. But one might well ask, why not just edit the resulting listing as a document? Not possible! Contemporary content management systems are based on a data flow from a "pure" source of a database, through controlling code and templates to produce a document as a result. The document isn't the data, it's the end result of an irreversible process. This problem, in this and many variants, is widespread and reveals an essential backwardness that a particular "computer scientist" mindset relating to what constitutes "data" and in particular it's relationship to order that makes what might be a straightforward question of editing a document into an over-engineered database.

Recently working with Nikolaos Vogiatzis whose research explores playful and radically subjective alternatives to the list, Vogiatzis was struck by how from the earliest specifications of HTML (still valid today) have separate elements (OL and UL) for "ordered" and "unordered" lists.

The representation of the list is not defined here, but a bulleted list for unordered lists, and a sequence of numbered paragraphs for an ordered list would be quite appropriate. Other possibilities for interactive display include embedded scrollable browse panels. [27]

Vogiatzis' surprise lay in the idea of a list ever being considered "unordered" (or in opposition to the language used in the specification, for order to ever be considered "insignificant"). Indeed in its suggested representation, still followed by modern web browsers, the only difference between the two visually is that UL items are preceded by a bullet symbol, while OL items are numbered.

The idea of ordering runs deep in programming practice where essentially different data structures are employed depending on whether order is to be maintained. The indexes of a "hash" table, for instance (also known as an associative array), are ordered in an unpredictable way governed by a representation's particular implementation. This data structure, extremely prevalent in contemporary programming practice sacrifices order to offer other kinds of efficiency (fast text-based retrieval for instance).

Data mining

In announcing Google's impending data center in Mons, Belgian prime minister Di Rupo invoked the link between the history of the mining industry in the region and the present and future interest in "data mining" as practiced by IT companies such as Google.

Whether speaking of bales of cotton, barrels of oil, or bags of words, what links these subjects is the way in which the notion of "raw material" obscures the labor and power structures employed to secure them. "Raw" is always relative: "purity" depends on processes of "refinement" that typically carry social/ecological impact.

Stripping language of order is an act of "disembodiment", detaching it from the acts of writing and reading. The shift from (human) reading to machine reading involves a shift of responsibility from the individual human body to the obscured responsibilities and seemingly inevitable forces of the "machine", be it the machine of a market or the machine of an algorithm.

"Unstructured" to the computer scientist, means non-conformant to particular forms of machine reading. "Structuring" then is a social process by which particular (additional) conventions are agreed upon and employed. Computer scientists often view text through the eyes of their particular reading algorithm, and in the process (voluntarily) blind themselves to the work practices which have produced and maintain these "resources".

Berners-Lee, in chastising his audience of web publishers to not only publish online, but to release "unadulterated" data belies a lack of imagination in considering how language is itself structured and a blindness to the need for more than additional technical standards to connect to existing publishing practices.

The City

Dennis Pohl: Smart cities, cities of knowledge

Formulating the Mundaneum

“We’re on the verge of a historic moment for cities” [30]

“We are at the beginning of a historic transformation in cities. At a time when the concerns about urban equity, costs, health and the environment are intensifying, unprecedented technological change is going to enable cities to be more efficient, responsive, flexible and resilient.”[31]

In 1927 Le Corbusier participated in the design competition for the headquarters of the League of Nations, but his designs were rejected. It was then that he first met his later cher ami Paul Otlet. Both were already familiar with each other’s ideas and writings, as evidenced by their use of schemes, but also through the epistemic assumptions that underlie their world views.

Before meeting Le Corbusier, Otlet was fascinated by the idea of urbanism as a science, which systematically organizes all elements of life in infrastructures of flows. He was convinced to work with Van der Swaelmen, who had already planned a world city on the site of Tervuren near Brussels in 1919.[32]

For Otlet it was the first time that two notions from different practices came together, namely an environment ordered and structured according to principles of rationalization and taylorization. On the one hand, rationalization as an epistemic practice that reduces all relationships to those of definable means and ends. On the other hand, taylorization as the possibility to analyze and synthesize workflows according to economic efficiency and productivity. Nowadays, both principles are used synonymously: if all modes of production are reduced to labour, then its efficiency can be rationally determined through means and ends.

“By improving urban technology, it’s possible to significantly improve the lives of billions of people around the world. […] we want to supercharge existing efforts in areas such as housing, energy, transportation and government to solve real problems that city-dwellers face every day.”[33]

In the meantime, in 1922, Le Corbusier developed his theoretical model of the Plan Voisin, which served as a blueprint for a vision of Paris with 3 million inhabitants. In the 1925 publication Urbanisme his main objective is to construct “a theoretically water-tight formula to arrive at the fundamental principles of modern town planning.”[34] For Le Corbusier “statistics are merciless things,” because they “show the past and foreshadow the future”[35], therefore such a formula must be based on the objectivity of diagrams, data and maps.

Moreover, they “give us an exact picture of our present state and also of former states; [...] (through statistics) we are enabled to penetrate the future and make those truths our own which otherwise we could only have guessed at.”[36] Based on the analysis of statistical proofs he concluded that the ancient city of Paris had to be demolished in order to be replaced by a new one. Nevertheless, he didn’t arrive at a concrete formula but rather at a rough scheme.

A formula that includes every atomic entity was instead developed by his later friend Otlet as an answer to the question he posed in Monde, on whether the world can be expressed by a determined unifying entity. This is Otlet’s dream: a “permanent and complete representation of the entire world,”[37] located in one place.

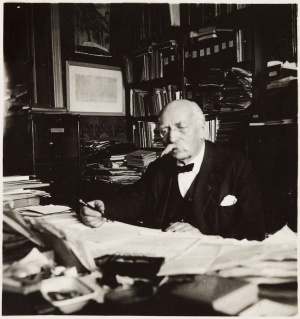

Early on Otlet understood the active potential of Architecture and Urbanism as a dispositif, a strategic apparatus, that places an individual in a specific environment and shapes his understanding of the world.[38] A world that can be determined by ascertainable facts through knowledge. He thought of his Traité de documentation: le livre sur le livre, théorie et pratique as an “architecture of ideas”, a manual to collect and organize the world's knowledge, hand in hand with contemporary architectural developments.Tim Berners-Lee: [...] Make a beautiful website, but first give us the unadulterated data, we want the data. We want unadulterated data. OK, we have to ask for raw data now. And I'm going to ask you to practice that, OK? Can you say "raw"?

Audience: Raw.

Tim Berners-Lee: Can you say "data"?

Audience: Data.

TBL: Can you say "now"?

Audience: Now!

TBL: Alright, "raw data now"!

[...]

Étant donné que les nouvelles formes modernistes et l'utilisation de matériaux propageaient l'abondance d'éléments décoratifs, Paul Otlet croyait en la possibilité du langage comme modèle de « données brutes », le réduisant aux informations essentielles et aux faits sans ambiguïté, tout en se débarrassant de tous les éléments inefficaces et subjectifs.

Template loop detected: The Smart City - City of Knowledge

“Information, from which has been removed all dross and foreign elements, will be set out in a quite analytical way. It will be recorded on separate leaves or cards rather than being confined in volumes,” which will allow the standardized annotation of hypertext for the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC).[39] Furthermore, the “regulation through architecture and its tendency of a total urbanism would help towards a better understanding of the book Traité de documentation and it's right functional and holistic desiderata.”[40] An abstraction would enable Otlet to constitute the “equation of urbanism” as a type of sociology (S): U = u(S), because according to his definition, urbanism “is an art of distributing public space in order to raise general human happiness; urbanization is the result of all activities which a society employs in order to reach its proposed goal; [and] a material expression of its organization.”[41] The scientific position, which determines all characteristic values of a certain region by a systematic classification and observation, was developed by the Scottish biologist and town planner Patrick Geddes, who Paul Otlet invited to present his Town Planning Exhibition to an international audience at the 1913 world exhibition in Gent.[42] What Geddes inevitably takes further is the positivist belief in a totality of science, which he unfolds from the ideas of Auguste Comte, Frederic Le Play and Elisée Reclus in order to reach a unified understanding of an urban development in a special context. This position would allow to represent the complexity of an inhabited environment through data.[43]

Thinking the Mundaneum

The only person that Otlet considered capable of the architectural realization of the Mundaneum was Le Corbusier, whom he approached for the first time in spring 1928. In one of the first letters he addressed the need to link “the idea and the building, in all its symbolic representation. […] Mundaneum opus maximum.” Aside from being a centre of documentation, information, science and education, the complex should link the Union of International Associations (UIA), which was founded by La Fontaine and Otlet in 1907, and the League of Nations. “A material and moral representation of The greatest Society of the nations (humanity);” an international city located on an extraterritorial area in Geneva.[44] Despite their different backgrounds, they easily understood each other, since they “did frequently use similar terms such as plan, analysis, classification, abstraction, standardization and synthesis, not only to bring conceptual order into their disciplines and knowledge organization, but also in human action.”[45] Moreover, the appearance of common terms in their most significant publications is striking. Such as spirit, mankind, elements, work, system and history, just to name a few. These circumstances led both Utopians to think the Mundaneum as a system, rather than a singular central type of building; it was meant to include as many resources in the development process as possible. Because the Mundaneum is “an idea, an institution, a method, a material corpus of works and collections, a building, a network,”[46] it had to be conceptualized as an “organic plan with the possibility to expand on different scales with the multiplication of each part.”[47] The possibility of expansion and an organic redistribution of elements adapted to new necessities and needs, is what guarantees the system efficiency, namely by constantly integrating more resources. By designing and standardizing forms of life up to the smallest element, modernism propagated a new form of living which would ensure the utmost efficiency. Otlet supported and encouraged Le Corbusier with his words: “The twentieth century is called upon to build a whole new civilization. From efficiency to efficiency, from rationalization to rationalization, it must so raise itself that it reaches total efficiency and rationalization. […] Architecture is one of the best bases not only of reconstruction (the deforming and skimpy name given to the whole of post-war activities) but of intellectual and social construction to which our era should dare to lay claim.”[48] Like the Wohnmaschine, in Corbusier’s famous housing project Unité d'habitation, the distribution of elements is shaped according to man's needs. The premise which underlies this notion is that man's needs and desires can be determined, normalized and standardized following geometrical models of objectivity.

“making transportation more efficient and lowering the cost of living, reducing energy usage and helping government operate more efficiently”[49]

Building the Mundaneum

In the first working phase, from March to September 1928, the plans for the Mundaneum seemed more a commissioned work than a collaboration. In the 3rd person singular, Otlet submitted descriptions and organizational schemes which would represent the institutional structures in a diagrammatic manner. In exchange, Le Corbusier drafted the architectural plans and detailed descriptions, which led to the publication N° 128 Mundaneum, printed by International Associations in Brussels.[50] Le Corbusier seemed a little less enthusiastic about the Mundaneum project than Otlet, mainly because of his scepticism towards the League of Nations, which he called a “misguided” and “pre-machinist creation.”[51] The rejection of his proposal for the Palace for the League of Nations in 1927, expressed with anger in a public announcement, might also play a role. However, the second phase, from September 1928 to August 1929, was marked by a strong friendship evidenced by the rise of the international debate after their first publications, letters starting with cher ami and their agreement to advance the project to the next level by including more stakeholders and developing the Cité mondiale. This led to the second publication by Paul Otlet, La Cité mondiale in February 1929, which unexpectedly traumatized the diplomatic environment in Geneva. Although both tried to organize personal meetings with key stakeholders, the project didn't find support for its realization, especially after Switzerland had withdrawn its offer of providing extraterritorial land for Cité mondiale. Instead, Le Corbusier focussed on his Ville Radieuse concept, which was presented at the 3rd CIAM meeting in Brussels in 1930.[52] He considered Cité mondiale as “a closed case”, and withdrew himself from the political environment by considering himself without any political color, “since the groups that gather around our ideas are, militaristic bourgeois, communists, monarchists, socialists, radicals, League of Nations and fascists. When all colors are mixed, only white is the result. That stands for prudence, neutrality, decantation and the human search for truth.”[53]

Governing the Mundaneum

Le Corbusier considered himself and his work “apolitical” or “above politics”.[54] Otlet, however, was more aware of the political force of his project. “Yet it is important to predict. To know in order to predict and to predict in order to control, was Comte's positive philosophy. Prediction doesn't cost a thing, was added by a master of contemporary urbanism (Le Corbusier).”[55] Lobbying for the Cité mondiale project, That prediction doesn't cost anything and is “preparing the ways for the coming years”, Le Corbusier wrote to Arthur Fontaine and Albert Thomas from the International Labor Organization that prediction is free and “preparing the ways for the coming years”.[56] Free because statistical data is always available, but he didn't seem to consider that prediction is a form of governing. A similar premise underlies the present domination of the smart city ideologies, where large amounts of data are used to predict for the sake of efficiency. Although most of the actors behind these ideas consider themselves apolitical, the governmental aspect is more than obvious. A form of control and government, which is not only biopolitical but rather epistemic. The data is not only used to standardize units for architecture, but also to determine categories of knowledge that restrict life to the normality of what can be classified. What becomes clear in this juxtaposition of Le Corbusier's and Paul Otlet's work is that the standardization of architecture goes hand in hand with an epistemic standardization because it limits what can be thought, experienced and lived to what is already there. This architecture has to be considered as an “epistemic object”, which exemplifies the cultural logic of its time.[57] By its presence it brings the abstract cultural logic underlying its conception into the everyday experience, and becomes with material, form and function an actor that performs an epistemic practice on its inhabitants and users. In this case: the conception that everything can be known, represented and (pre)determined through data.

Natacha Roussel: Times in Brussels

The ambitious project of the Mundaneum was imagined by Paul Otlet with support of Henri La Fontaine at the end of the 19th century. At that time colonialism was at its height, bringing a steady stream of income to occidental countries which created a sense of security that made everything seem possible. According to some of the most forward thinking persons of the time it felt as if the intellectual and material benefits of rational thinking could universally become the source of all goods. Far from any actual move towards independence, the first tensions between colonial/commercial powers were starting to manifest themselves. Already some conflicts erupted, mainly to defend commercial interests such as during the Fashoda crisis and the Boers war. The sense of strength brought to colonial powers by the large influx of money was however quickly tempered by World War I that was about to shake up modern European society.

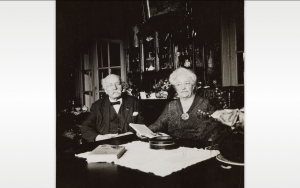

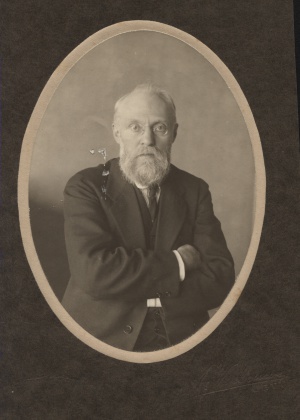

In this context Henri La Fontaine, energised by Paul Otlet's encompassing view of classification systems and standards, strongly associates the Mundaneum project with an ideal of world peace. This was a conscious process of thought; they believed that this universal archive of all knowledge represented a resource for the promotion of education towards the development of better social relations. While Otlet and La Fontaine were not directly concerned with economical and colonial issues, their ideals were nevertheless fed by the wealth of the epoch. The Mundaneum archives were furthermore established with a clear intention, and a major effort was done to include documents that referred to often neglected topics or that could be considered as alternative thinking, such as the well known archives of the feminist movement in Belgium and information on anarchism and pacifism. In line with the general dynamism caused by a growing wealth in Europe at the turn of the century, the Mundaneum project seemed to be always growing in size and ambition. It also clearly appears that the project was embedded in the international and 'politico-economical' context of its time and in many aspects linked to a larger movement that engaged civil society towards a proto-structure of networked society. Via the development of infrastructures for communication and international regulations, Henri La Fontaine was part of several international initiatives. For example he launched the 'Bureau International de la paix' as early as 1907 and a few years after, in 1910, the 'International Union of Associations'. Overall his interventions helped to root the process of archive collection in a larger network of associations and regulatory structures. Otlet's view of archives and organisation extended to all domains and La Fontaine asserted that general peace could be achieved through social development by the means of education and access to knowledge. Their common view was nurtured by an acute perception of their epoch, they observed and often contributed to most of the major experiments that were triggered by the ongoing reflection about the new organisation modalities of society.

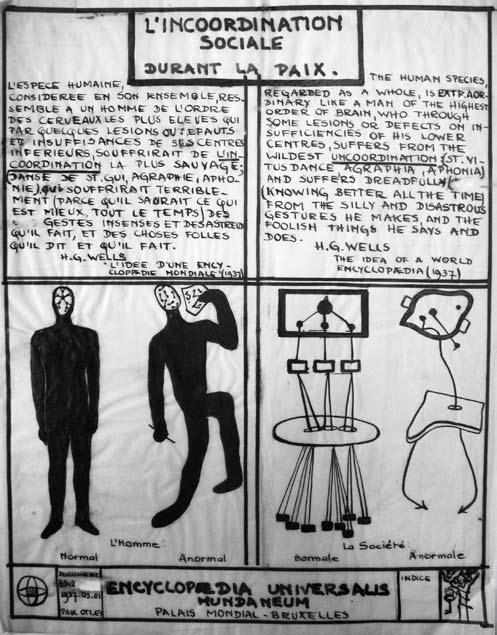

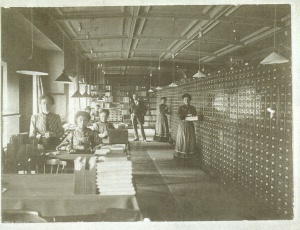

Museology merged with the International Institute of Bibliography (IIB) which had its offices in the same building. The ever-expanding index card catalog had already been accessible to the public since 1914. The project would be later known as the World Palace or Mundaneum. Here, Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine started to work on their Encyclopaedia Universalis Mundaneum, an illustrated encyclopaedia in the form of a mobile exhibition.

« Un droit nouveau doit remplacer alors le droit ancien pour préparer et organiser une nouvelle répartition. La “question sociale” a posé le problème à l’intérieur ; “la question internationale” pose le même problème à l’extérieur entre peuples. Notre époque a poursuivi une certaine socialisation de biens. […] Il s’agit, si l’on peut employer cette expression, de socialiser le droit international, comme on a socialisé le droit privé, et de prendre à l’égard des richesses naturelles des mesures de “mondialisation”. »[59].

The approaches of La Fontaine and Otlet already bear certain differences, as one (Lafontaine) emphasises an organisation based on local civil society structures which implies direct participation, while the other (Otlet) focuses more on management and global organisation managed by a regulatory framework. It is interesting to look at these early concepts that were participating to a larger movement called 'the first mondialisation', and understand how they differ from current forms of globalisation which equally involve private and public instances and various infrastructures.

The project of Otlet and Lafontaine took place in an era of international agreements over communication networks. It is known and often a subject of fascination that the global project of the Mundaneum also involved the conception of a technical infrastructure and communication systems that were conceived in between the two World Wars. Some of them such as the Mondothèque were imagined as prospective possibilities, but others were already implemented at the time and formed the basis of an international communication network, consisting of postal services and telegraph networks. It is less acknowledged that the epoch was also a time of international agreements between countries, structuring and normalising international life; some of these structures still form the basis of our actual global economy, but they are all challenged by private capitalist structures. The existing postal and telegraph networks covered the entire planet, and agreements that regulated the price of the stamp allowing for postal services to be used internationally, were recent. They certainly were the first ones during where international agreements regulated commercial interests to the benefit of individual communication. Henri Lafontaine directly participated in these processes by asking for the postal franchise to be waived for the transport of documents between international libraries, to the benefit of among others the Mundaneum. Lafontaine was also an important promoter of larger international movements that involved civil society organisations; he was the main responsible for the 'Union internationale des associations', that acted as a network of information-sharing, setting up modalities for exchange to the general benefit of civil society. Furthermore, concerns were raised to rethink social organisation that was harmed by industrial economy and this issue was addressed in Brussels by the brand new discipline of sociology. The 'Ecole de Bruxelles'[60] in which Otlet and La Fontaine both took part was already very early on trying to formulate a legal discourse that could help address social inequalities, and eventually come up with regulations that could help 're-engineer' social organisation.

The Mundaneum project differentiates itself from contemporary enterprises such as Google, not only by its intentions, but also by its organisational context as it clearly inscribed itself in an international regulatory framework that was dedicated to the promotion of local civil society. How can we understand the similarities and differences between the development of the Mundaneum project and the current knowledge economy? The timeline below attempts to re-situate the different events related to the rise and fall of the Mundaneum in order to help situate the differences between past and contemporary processes.

| DATE | EVENT | TYPE | SCALE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1865 | The International Union of telegraph, is set up it is an important element of the organisation of a mondial communication network and will further become the International Telecommunication Union (UTI)[61] that is still active in regulating and standardizing radio-communication. | STANDARD | WORLD |

| 1870 | Franco-Prussian war. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1874 | The ONU creates the General Postal Union[62] and aims to federate international postal distribution. | STANDARD | WORLD |

| 1875 | General Conference on Weights and Measures in Sèvres, France. | STANDARD | WORLD |

| 1882 | Triple Alliance, renewed in 1902. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1889 | Henri Lafontaine creates La Société Belge de l'arbitrage et de la paix. | EVENT | NATION |

| 1890's | First colonial wars (Fachoda crisis, Boers war ...). | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1890 | Henri Lafontaine meets Paul Otlet. | PERSON | CITY |

| 1891 | Franco-Russian entente', preliminary to the Triple entente that will be signed in 1907. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1891 | Henri Lafontaine publishes an essay Pour une bibliographie de la paix. | PUBLICATION | NATION |

| 1893 | Otlet and Lafontaine start together the Office International de Bibliologie Sociologique (OIBS). | ASSOCIATION | CITY |

| 1894 | Henri Lafontaine is elected senator of the province of Hainaut and later senator of the province of Liège-Brabant. | EVENT | NATION |

| 1895 2-4 September | First Conférence de Bibliographie at which it is decided to create the Institut International de Bibliographie (IIB) founded by Henri La Fontaine. | ASSOCIATION | CITY |

| 1900 | Congrès bibliographique international in Paris. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1903 | Creation of the international Women's suffrage alliance (IWSA) that will later become the International Alliance of Women. | ASSOCIATION | WORLD |

| 1904 | Entente cordiale between France and England which defines their mutual zone of colonial influence in Africa. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1905 | First Moroccan crisis. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1907 June | Otlet and Lafontaine organise a Central Office for International Associations that will become the International Union of Associations (IUA) at the first Congrès mondial des associations internationales in Brussels in May 1910. | ASSOCIATION | CITY |

| 1907 | Henri Lafontaine is elected president of the Bureau international de la paix that he previously initiated. | PERSON | NATION |

| 1908 July | Congrès bibliographique international in Brussels. | EVENT | CITY |

| 1910 May | Official Creation of the International union of associations (IUA). In 1914, it federates 230 organizations, a little more than half of them still exist. The IUA promotes internationalist aspirations and desire for peace. | ASSOCIATION | WORLD |

| 1910 25-27 August | Le Congrès International de Bibliographie et de Documentation deals with issues of international cooperation between non-governmental organizations and with the structure of universal documentation. | ASSOCIATION | WORLD |

| 1911 | More than 600 people and institutions are listed as IIB members or refer to their methods, specifically the UDC. | ASSOCIATION | WORLD |

| 1913 | Henri Lafontaine is awarded the Nobel Price for Peace. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1914 | Germany declares war to France and invades Belgium. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1916 | Lafontaine publishes The great solution: magnissima charta while in exile in the United States. | PUBLICATION | WORLD |

| 1919 | Opening of the Mundaneum or Palais Mondial at the Cinquantenaire park. | EVENT | CITY |

| 1919 June 28 | The Traité de Versailles marks the end of World War I and creation of the Societé Des Nations (SDN) that will later become the United Nations (UN). | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1924 | Creation (within the IIB), of the Central Classification Commission focusing on the development of the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC). | ASSOCIATION | NATION |

| 1931 | The IIB becomes the International Institute of documentation (IID) and in 1938 and is named International Federation of documentation (IDF). | ASSOCIATION | WORLD |

| 1934 | Publication of Otlet's book Traité de documentation. | PUBLICATION | WORLD |

| 1934 | The Mundaneum is closed after a governmental decision. A part of the archives are moved to Rue Fétis 44, Brussels, home of Paul Otlet. | MOVE | HOUSE |

| 1939 September | Invasion of Poland by Germany, start of World War II. | EVENT | WORLD |

| 1941 | Some files from the Mundaneum collections concerning international associations, are transferred to Germany. They are assumed to have propaganda value. | MOVE | WORLD |

| 1944 | Death of Paul Otlet. He is buried in Etterbeek cemetery. | EVENT | CITY |

| 1947 | The International Telecomunication Union (UTI) is attached to the UN. | STANDARD | GLOBE |

| 1956 | Two separate ITU committees, the Consultive Committee for International Telephony (CCIF) and the Consultive Committee for International Telegraphy (CCIT) are joined to form the CCITT, an institute to create standards, recommendations and models for telecommunications. | STANDARD | GLOBE |

| 1963 | American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is developed. | STANDARD | GLOBE |

| 1966 | The ARPANET project is initiated. | ASSOCIATION | NATION |

| 1974 | Telenet, the first public version of the Internet founded. | STANDARD | WORLD |

| 1986 | First meeting of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) , the US-located informal organization that promotes open standards along the lines of "rough consensus and running code". | STANDARD | GLOBE |

| 1992 | Creation of The Internet Society, an American association with international vocation. | STANDARD | WORLD |

| 1993 | Elio Di Rupo organises the transport of the Mundaneum archives from Brussels to 76 rue de Nimy in Mons. | MOVE | NATION |

| 2012 | Failure of the World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) to reach an international agreement on Internet regulation. | STANDARD | GLOBE |

Additional timelines

- https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/la-premiere-guerre-mondiale

- http://www.telephonetribute.com/timeline.html

- https://www.reseau-canope.fr/savoirscdi/societe-de-linformation/le-monde-du-livre-et-de-la-presse/histoire-du-livre-et-de-la-documentation/biographies/paul-otlet.html

- http://monoskop.org/Otlet

- http://archives.mundaneum.org/fr/historique

References

Mondothèque: Location, location, location

Its tragic demise was unfortunately equally at home in Brussels. Already in Otlet's lifetime, the project fell prey to the dis-interest of its former patrons, not surprising after World War I had shaken their confidence in the beneficial outcomes of a global knowledge infrastructure. A complex entanglement of dis-interested management and provincial politics sent the numerous boxes and folders on a long trajectory through Brussels, until they finally slipped out of the city. It is telling that the Capital of Europe has been unable to hold on to its pertinent past.

This tour is a kind of itinerant monument to the Mundaneum in Brussels. It takes you along the many temporary locations of the archives, guided by the words of care-takers, reporters and biographers that have crossed it's path. Following the increasingly dispersed and dwindling collection through the city and centuries, you won't come across any material trace of its passage, though you might discover many unknown corners of Brussels.1919: Musée international