Une histoire préventive du Google Cultural Institute

From Mondothèque

Revision as of 11:34, 21 March 2016 by FS (talk | contribs) (Created page with "__NOTOC__ author::Geraldine Juárez == I. Organizing information is never innocent == <onlyinclude>Six years ago, Google, an Alphabet company, l...")

I. Organizing information is never innocent

Six years ago, Google, an Alphabet company, launched a new project: The Google Art Project. The official history, the one written by Google and distributed mainly through tailored press releases and corporate news bits, tells us that it all started as “a 20% project within Google in 2010 and had its first public showing in 2011. It was 17 museums, coming together in a very interesting online platform, to allow users to essentially explore art in a very new and different way."[1] While Google Books faced legal challenges and the European Commission launched its antitrust case against Google in 2010, the Google Art Project, not coincidentally, scaled up gradually, resulting in the Google Cultural Institute with headquarters in Paris, “whose mission is to make the world's culture accessible online.”[2]

The Google Cultural Institute is strictly divided in Art Project, Historical Moments and World Wonders, roughly corresponding to fine art, world history and material culture. Technically, the Google Cultural Institute can be described as a database that powers a repository of high-resolution images of fine art, objects, documents and ephemera, as well as information about and from their ‘partners’ - the public museums, galleries and cultural institutions that provide this cultural material - such as 3D tour views and street-view maps. So far and counting, the Google Cultural Institute hosts 177 digital reproductions of selected paintings in gigapixel resolution and 320 3D versions of different objects, together with multiple thematic slide shows curated in collaboration with their partners or by their users.

According to their website, in their ‘Lab’ they develop the “new technology to help partners publish their collections online and reach new audiences, as seen in the Google Art Project, Historic Moments and World Wonders initiatives.” These services are offered – not by chance – as a philanthropic service to public institutions that increasingly need to justify their existence in face of cuts and other managerial demands of the austerity policies in Europe and elsewhere.

The Google Cultural Institute “would be unlikely, even unthinkable, absent the chronic and politically induced starvation of publicly funded cultural institutions even throughout the wealthy countries”[3]. It is important to understand that what Google is really doing is bankrolling the technical infrastructure and labour needed to turn culture into data so it can be easily managed and feed all kind of products needed in the neoliberal city to promote and exploit these cultural ‘assets’, in order to compete with other urban centres in the global stage, but also, to feed Google’s unstoppable accumulation of information.

The head of the Google Cultural Institute knows there are a lot of questions about their activities but Alphabet chose to label legitimate critiques as misunderstandings: “This is our biggest battle, this constant misunderstanding of why the Cultural Institute actually exists.”[4] The Google Cultural Institute, much like many other cultural endeavours of Google like Google Books and their Digital Revolution art exhibition, has been subject to a few but much needed critiques, such as Powered by Google: Widening Access and Tightening Corporate Control (Schiller & Yeo 2014), an in-depth account of the origins of this cultural intervention and its role in the resurgence of welfare capitalism, “where people are referred to corporations rather than states for such services as they receive; where corporate capital routinely arrogates to itself the right to broker public discourse; and where history and art remain saturated with the preferences and priorities of elite social classes.”[5]

Known as one, if not the first essay that dissects Google's use of information and the rhetoric of democratization behind it to reorganize cultural public institutions as a “site of profit-making”, Schiller & Yeo’s text is fundamental to understand the evolution of the Google Cultural Institute within the historical context of digital capitalism, where the global dependency in communication and information technologies is directly linked to the current crisis of accumulation and where Google's archive fever “evinces a breath-taking cultural and ideological range.”[6]

II. Who colonizes the colonizers?

The Google Cultural Institute is a complex subject of interest since it reflects the colonial impulses embedded in the scientific and economic desires that formed the very collections which the Google Cultural Institute now mediates and accumulates in its database.

Who colonizes the colonizers? It is a very difficult issue which I have raised before in an essay dedicated to the Google Cultural Institute, Alfred Russel Wallace and the colonial impulse behind archive fevers from the 19th but also the 21st century. I have no answer yet. But a critique of the Google Cultural Institute where their motivations are interpreted as merely colonialist would be misleading and counterproductive. It is not their goal to slave and exploit whole populations and its resources in order to impose a new ideology and civilise barbarians in the same sense and way that European countries did during the Colonization. Additionally, it would be unfair and disrespectful to all those who still have to deal with the endless effects of Colonization, that have exacerbated with the expansion of economic globalisation.

The conflation of technology and science that has produced the knowledge to create such an entity as Google and its derivatives, such as the Cultural Institute, together with the scale of its impact on a society where information technology is the dominant form of technology, makes technocolonialism a more accurate term to describe Google's cultural interventions from my perspective.

Although technocolonization shares many traits and elements with the colonial project, starting with the exploitation of materials needed to produce information and media technologies – and the related conflicts that this produces –, information technologies still differ from ships and canons. However, the commercial function of maritime technologies is the same as the free – as in free trade – services deployed by Google or Facebook’s drones beaming internet in Africa, although the networked aspect of information technologies is significantly different at the infrastructure level.

There is no official definition of technocolonialism, but it is important to understand it as a continuation of the idea of Enlightenment that gave birth to the impulse to collect, organise and manage information in the 19th century. My use of this term aims to emphasize and situate contemporary accumulation and management of information and data within a technoscientific landscape driven by “profit above else” as a “logical extension of the surplus value accumulated through colonialism and slavery.”[7]

Unlike in colonial times, in contemporary technocolonialism the important narrative is not the supremacy of a specific human culture. Technological culture is the saviour. It doesn’t matter if the culture is Muslim, French or Mayan, the goal is to have the best technologies to turn it into data, rank it, produce content from it and create experiences that can be monetized.

It only makes sense that Google, a company with a mission of to organise the world’s information for profit, found ideal partners in the very institutions that were previously in charge of organising the world’s knowledge. But as I pointed out before, it is paradoxical that the Google Cultural Institute is dedicated to collect information from museums created under Colonialism in order to elevate a certain culture and way of seeing the world above others. Today we know and are able to challenge the dominant narratives around cultural heritage, because these institutions have an actual record in history and not only a story produced for the ‘about’ section of a website, like in the case of the Google Cultural Institute.

“What museums should perhaps do is make visitors aware that this is not the only way of seeing things. That the museum – the installation, the arrangement, the collection – has a history, and that it also has an ideological baggage”[8]. But the Google Cultural Institute is not a museum, it is a database with an interface that enables to browse cultural content. Unlike the prestigious museums it collaborates with, it lacks a history situated in a specific cultural discourse. It is about fine art, world wonders and historical moments in a general sense. The Google Cultural Institute has a clear corporate and philanthropic mission but it lacks a point of view and a defined position towards the cultural material that it handles. This is not surprising since Google has always avoided to take a stand, it is all techno-determinism and the noble mission of organising the world’s information to make the world better. But “brokering and hoarding information are a dangerous form of techno-colonialism.”[8]

Searching for a cultural narrative beyond the Californian ideology, Alphabet's search engine found in Paul Otlet and the Mundaneum the perfect cover to insert their philanthropic services in the history of information science beyond Silicon Valley. After all, they understand that “ownership over the historical narratives and their material correlates becomes a tool for demonstrating and realizing economic claims”.[9]

After establishing a data centre in the Belgian city of Mons, home of the Mundaneum, Google lent its support to “the Mons 2015 adventure, in particular by working with our longtime partners, the Mundaneum archive. More than a century ago, two visionary Belgians envisioned the World Wide Web’s architecture of hyperlinks and indexation of information, not on computers, but on paper cards. Their creation was called the Mundaneum.”[10] VERSION FRANCAISE

On the occasion of the 147th birthday of Paul Otlet, a Doodle in the homepage of the Alphabet spelled the name of its company using the ‘drawers of the Mundaneum’ to form the words G O O G L E: “Today’s Doodle pays tribute to Paul’s pioneering work on the Mundaneum. The collection of knowledge stored in the Mundaneum’s drawers are the foundational work for everything that happens at Google. In early drafts, you can watch the concept come to life.”[11]

III. Google Cultural History

The dematerialisation of public collections using infrastructure and services bankrolled by private actors like the GCI, needs to be questioned and analyzed further in the context of heterotopic institutions, to understand the new forms taken by the endless tension between knowledge/power at the core of contemporary archivalism, where the architecture of the interface replaces and acts on behalf of the museum, and the body of the visitor is reduced to the fingers of a user capable of browsing endless cultural assets.

At a time when cultural institutions should be decolonised instead of googlified, it is vital to discuss a project such as the Google Cultural Institute and its continuous expansion – which is inversely proportional to the failure of the governments and the passivity of institutions seduced by gadgets[12].

However, the dialogue is fragmented between limited academic accounts, corporate press releases, isolated artistic interventions, specialised conferences and news reports. Femke Snelting suggests that we must “find the patience to build a relation to these histories in ways that make sense.” To do so, we need to excavate and assemble a better account of the history of the Google Cultural Institute. Building upon Schiller & Yeo’s seminal text, the following timeline is my contribution to this task and an attempt to put together the pieces, by situating them in a broader economic and political context beyond the official history told by the Google Cultural Institute. A closer inspection of the events reveals that the escalation of Alphabet's cultural interventions often emerge after a legal challenge against their economic hegemony in Europe was initiated.

2009

Eric Schmidt visits Iraq

A news report from the Wall Street Journal[13] as well as an AP report on Youtube[14] confirm the new Google venture in the field of historical collections. The executive chairman of Alphabet declared: “I can think of no better use of our time and our resources to make the images and ideas from your civilization, from the very beginning of time, available to a billion people worldwide.”

A detailed account and reflection of this visit, its background and agenda can be found in Powered by Google: Widening Access and Tightening Corporate Control. (Schiller & Yeo 2014)

France reacts against Google Books

In relation to the Google Books dispute in Europe, Reuters reported in 2009 that France's ex-president Nicolas Sarkozy “pledged hundreds of millions of euros toward a separate digitization program, saying he would not permit France to be “stripped of our heritage to the benefit of a big company, no matter how friendly, big or American it is.”[15]

Although the reactionary and nationalistic agenda of Sarkozy should not be celebrated, it is important to note that the first open attack on Google’s cultural agenda came from the French government. Four years later, the Google Cultural Institute establishes its headquarters in Paris.

2010

European Commission launches an antitrust investigation against Google.

The European Commission has decided to open an antitrust investigation into allegations that Google Inc. has abused a dominant position in online search, in violation of European Union rules (Article 102 TFEU). The opening of formal proceedings follows complaints by search service providers about unfavourable treatment of their services in Google's unpaid and sponsored search results coupled with an alleged preferential placement of Google's own services. This initiation of proceedings does not imply that the Commission has proof of any infringements. It only signifies that the Commission will conduct an in-depth investigation of the case as a matter of priority.[16]

The Google Art Project starts as a 20% project under the direction of Amit Sood.

According to the Guardian[17], and other news reports, Google's cultural project is started by passionate art “googlers”.

Google announces its plans to build a European Cultural Institute in France

Referring to France as one of the most important centres for culture and technology, Google CEO Eric Schmidt formally announces the creation of a centre "dedicated to technology, especially noting the promotion of past, present and future European cultures."[18]

2011

Google Art Project Launches in Tate London.

In February the new ‘product’ is officially presented. The introduction[19] emphasises that it started as a 20% project, meaning a project that lacked corporate mandate.

According to the “Our Story”[20] section of the Google Cultural Institute, the history of the Google Art Project starts with the integration of 140,000 assets from the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Centre, followed by the inclusion of the Nelson Mandela Archives in the Historical Moments section of the Google Cultural Institute.

Later in August, Eric Schmidt declares that education should bring art and science together just like in “the glory days of the Victorian Era”.[21]

2012

EU data authorities initiate a new investigation into Google and their new terms of use.

At the request of the French authorities, the European Union initiates an investigation against Google, related to the breach of data privacy due to the new terms of use published by Google on 1 March 2012.[22]

The Google Cultural Institute continues to digitalize cultural ‘assets’.

According to the Google Cultural Institute website, 151 partners join the Google Art Project including France's Musée D’Orsay. The World Wonders section is launched including partnerships with the likes of UNESCO. By October, the platform is rebranded and re-launched including over 400+ partners.

2013

Google Cultural Institute headquarters opens in Paris.

On 10 December, the new French headquarters open in 8 rue de Londres. The French Minister Aurélie Filippetti cancels her attendance as she doesn’t “wish to appear as a guarantee for an operation that still raises a certain number of questions."[23]

British tax authorities initiate investigation into Google's tax scheme

HM Customs and Revenue Committee inquiry brands Google's tax operations in the UK via Ireland as "devious, calculated and, in my view, unethical".[24]

2014

European Court Of Justice rules on the “right to be forgotten” against Google.

The controversial ruling holds search engines responsible for the personal data that it handles and under European Law the court ruled “that the operator is, in certain circumstances, obliged to remove links to web pages that are published by third parties and contain information relating to a person from the list of results displayed following a search made on the basis of that person’s name. The Court makes it clear that such an obligation may also exist in a case where that name or information is not erased beforehand or simultaneously from those web pages, and even, as the case may be, when its publication in itself on those pages is lawful.”[25]

Digital Revolution at Barbican UK

Google sponsors the exhibition Digital Revolution[26] and commission artworks under the brand “Dev-art: art made with code.[27]”. The exhibition later tours to the Tekniska Museet in Stockholm.[28]

Google Cultural Institute's “The Lab” Opens

“Here creative experts and technology come together share ideas and build new ways to experience art and culture.”[29]

Google expressed its plans to support the city of Mons, European Capital of Culture in 2015.

A press release from Google[30] describes the new partnership with the Belgian city of Mons as a result of their position as local employer and investor in the city, since one of their two major data centres in Europe is located there.

2015

EU Commission sends Statement of Objections to Google.

The European Commission has sent a Statement of Objections to Google alleging the company has abused its dominant position in the markets for general internet search services in the European Economic Area (EEA) by systematically favouring its own comparison shopping product in its general search results pages.”[31]Google rejects the accusations as “wrong as a matter of fact, law and economics”.[32]

European Commission starts investigation into Android.

The Commission will assess if, by entering into anticompetitive agreements and/or by abusing a possible dominant position, Google has illegally hindered the development and market access of rival mobile operating systems, mobile communication applications and services in the European Economic Area (EEA). This investigation is distinct and separate from the Commission investigation into Google's search business.[33]

Google Cultural Institute continues to expand.

According to the ‘Our Story’ section of the Google Cultural Institute, the Street Art project now has 10,000 assets. A new extension displays art from the Google Art Project in the Chrome browser and “art lovers can wear art on their wrists via Android art”. By August, the project has more than 850 partners using their tools, 4.7 million assets in its collection and more than 1500 curated exhibitions.

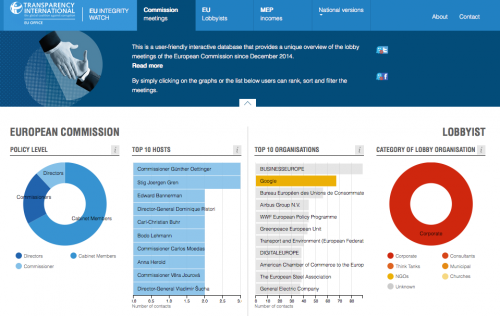

Transparency International reveals Google as second biggest corporate lobbyists operating in Brussels. [34]

Alphabet Inc. is established on October 2nd.

“Alphabet Inc. (commonly known as Alphabet) is an American multinational conglomerate created in 2015 as the parent company of Google and several other companies previously owned by or tied to Google.”[35]

Paul Otlet Doodle and Mundaneum-Google exhibitions.

Google creates a doodle for their homepage on the occasion of the 147th birthday of Paul Otlet[36] and produces the slide shows Towards the Information Age, Mapping Knowledge and The 100th Anniversary of a Nobel Peace Prize, all hosted by the Google Cultural Institute.

“The Mundaneum and Google have worked closely together to curate 9 exclusive online exhibitions for the Google Cultural Institute. The team behind the reopening of the Mundaneum this year also worked with the Cultural Institute engineers to launch a dedicated mobile app.”[37]

Google Cultural Institute partners with the British Museum.

The British Museum announce a “unique partnership” where over 4,500 assets can be “seen online in just a few clicks”. In the official press release, the director of the museum, Neil McGregor, said “The world today has changed, the way we access information has been revolutionised by digital technology. This enables us to gives the Enlightenment ideal on which the Museum was founded a new reality. It is now possible to make our collection accessible, explorable and enjoyable not just for those who physically visit, but to everybody with a computer or a mobile device. ”[38]

Google Cultural Institute adds a Performing Arts section.

Over 60 performing arts (dance, drama, music, opera) organizations and performers join the assets collection of the Google Cultural Institute [39]

2016

- ↑ Caines, Matthew. “Arts head: Amit Sood, director, Google Cultural Institute” The Guardian. Dec 3, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/culture-professionals-blog/2013/dec/03/amit sood-google-cultural-institute-art-project

- ↑ Google Paris. Accessed Dec 22, 2016 http://www.google.se/about/careers/locations/paris/

- ↑ Schiller, Dan & Yeo, Shinjoung. “Powered By Google: Widening Access And Tightening Corporate Control.” (In Aceti, D. L. (Ed.). Red Art: New Utopias in Data Capitalism: Leonardo Electronic Almanac, Vol. 20, No. 1. London: Goldsmiths University Press. 2014):48

- ↑ Down, Maureen. “The Google Art Heist”. The New York Times. Sept 12, 2015 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/opinion/sunday/the-google-art-heist.html

- ↑ Schiller, Dan & Shinjoung Yeo. “Powered By Google: Widening Access And Tightening Corporate Control.”, 48

- ↑ Schiller, Dan & Yeo, Shinjoung. “Powered By Google: Widening Access And Tightening Corporate Control.”, 48

- ↑ Davis, Heather & Turpin, Etienne, eds. Art in the Antropocene (London: Open Humanities Press. 2015), 7

- ↑ Bush, Randy. Psg.com On techno-colonialism. (blog) June 13, 2015. Accessed Dec 22, 2015 https://psg.com/on-technocolonialism.html

- ↑ Starzmann, Maria Theresia. “Cultural Imperialism and Heritage Politics in the Event of Armed Conflict: Prospects for an ‘Activist Archaeology’”. Archeologies. Vol. 4 No. 3 (2008):376

- ↑ Echikson,William. Partnering in Belgium to create a capital of culture (blog) March 20, 2014. Accessed Dec 22, 2015 http://googlepolicyeurope.blogspot.se/2014/03/partnering-in-belgium-to-create-capital.html

- ↑ Google. Mundaneum co-founder Paul Otlet's 147th Birthday (blog) August 23, 2015. Accessed Dec 22, 2015 http://www.google.com/doodles/mundaneum-co-founder-paul-otlets-147th-birthday

- ↑ eg. https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/thelab/#experiments

- ↑ Lavallee, Andrew. “Google CEO: A New Iraq Means Business Opportunities.” Wall Street Journal. Nov 24, 2009 http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2009/11/24/google-ceo-a-new-iraq-means-business-opportunities/

- ↑ Associated Press. Google Documents Iraqi Museum Treasures (on-line video November 24, 2009) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqtgtdBvA9k

- ↑ Jarry, Emmanuel. “France's Sarkozy takes on Google in books dispute.” Reuters. December 8, 2009. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-google-sarkozy-idUSTRE5B73E320091208

- ↑ European Commission. Antitrust: Commission probes allegations of antitrust violations by Google (Brussels 2010) http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-10-1624_en.htm

- ↑ Caines, Matthew. “Arts head: Amit Sood, director, Google Cultural Institute” The Guardian. December 3, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/culture-professionals-blog/2013/dec/03/amit sood google-cultural-institute-art-project

- ↑ Cyrus, Farivar. "Google to build R&D facility and 'European cultural center' in France.” Deutsche Welle. September 9, 2010. http://www.dw.com/en/google-to-build-rd-facility-and-european-cultural-center-in-france/a-5993560

- ↑ Google Art Project. Art Project V1 - Launch Event at Tate Britain. (on-line video February 1, 2011) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NsynsSWVvnM

- ↑ Google Cultural Institute. Accessed Dec 18, 2015. https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/about/partners/

- ↑ Robinson, James. “Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google, condemns British education system” The Guardian. August 26, 2011 http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/aug/26/eric-schmidt-chairman-google-education

- ↑ European Commission. Letter addressed to Google by the Article 29 Group (Brussels 2012) http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/article-29/documentation/other-document/files/2012/20121016_letter_to_google_en.pdf

- ↑ Willsher, Kim. “Google Cultural Institute's Paris opening snubbed by French minister.” The Guardian. December 10, 2013 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/10/google-cultural-institute-france-minister-snub

- ↑ Bowers, Simon & Syal, Rajeev. “MP on Google tax avoidance scheme: 'I think that you do evil'”. The Guardian. May 16, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/may/16/google-told-by-mp you-do-do-evil

- ↑ Court of Justice of the European Union. Press-release No 70/14 (Luxembourg, 2014) http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2014-05/cp140070en.pdf

- ↑ Barbican. “Digital Revolution.” Accessed December 15, 2015 https://www.barbican.org.uk/bie/upcoming-digital-revolution

- ↑ Google. “Dev Art”. Accessed December 15, 2015 https://devart.withgoogle.com/

- ↑ Tekniska Museet. “Digital Revolution.” Accessed December 15, 2015 http://www.tekniskamuseet.se/1/5554.html

- ↑ Google Cultural Institute. Accessed December 15, 2015. https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/thelab/

- ↑ Echikson,William. Partnering in Belgium to create a capital of culture (blog) March 20, 2014. Accessed Dec 22, 2015 http://googlepolicyeurope.blogspot.se/2014/03/partnering-in-belgium-to-create-capital.html

- ↑ European Commission. Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Google on comparison shopping service; opens separate formal investigation on Android. (Brussels 2015) http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-4780_en.htm

- ↑ Yun Chee, Foo. “Google rejects 'unfounded' EU antitrust charges of market abuse” Reuters. (August 27, 2015) http://www.reuters.com/article/us-google-eu-antitrust-idUSKCN0QW20F20150827

- ↑ European Commission. Antitrust: Commission sends Statement

- ↑ Transparency International. Lobby meetings with EU policy-makers dominated by corporate interests (blog) June 24, 2015. Accessed December 22, 2015. http://www.transparency.org/news/pressrelease/lobby_meetings_with_eu_policy_makers_dominated_by_corporate_interests

- ↑ Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. s.v. “Alphabet Inc,” (accessed Jan 25, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alphabet_Inc.

- ↑ Google. Mundaneum co-founder Paul Otlet's 147th Birthday (blog) August 23, 2015. Accessed Dec 22, 2015 http://www.google.com/doodles/mundaneum-co-founder-paul-otlets-147th-birthday

- ↑ Google. Mundaneum co-founder Paul Otlet's 147th Birthday

- ↑ The British Museum. The British Museum’s unparalleled world collection at your fingertips. (blog) November 12, 2015. Accessed December 22, 2015. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/press_releases/2015/with_google.aspx

- ↑ Sood, Amit. Step on stage with the Google Cultural Institute (blog) December 1, 2015. Accessed December 22, 2015. https://googleblog.blogspot.se/2015/12/step-on-stage-with-google-cultural.html