Difference between revisions of "The Itinerant Archive (print)"

From Mondothèque

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{NOTOC}} | {{NOTOC}} | ||

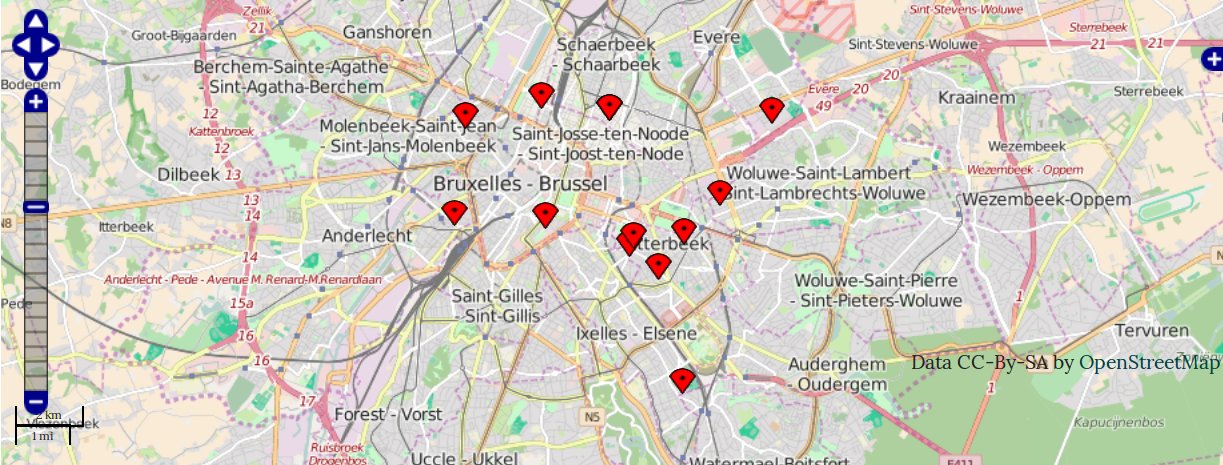

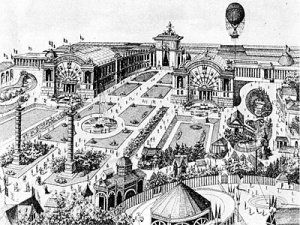

| − | <div class="intro">The project of the [[Mundaneum]] and its many [[:Property:Person|protagonists]] is undoubtedly linked to the context of early | + | <div class="intro">The project of the [[Mundaneum]] and its many [[:Property:Person|protagonists]] is undoubtedly linked to the context of early 20th century [[Brussels]]. [[King Leopold II]], in an attempt to awaken his countries' desire for greatness, let a steady stream of capital flow into the city from his private colonies in Congo. Located on the crossroad between France, Germany, The Netherlands and The United Kingdom, the Belgium capital formed a fertile ground for ambitious institutional projects with international ambitions, such as the Mundaneum. |

| − | Its tragic demise was unfortunately equally at home in Brussels. Already in Otlet's lifetime, the project fell prey to the dis-interest of its former patrons, not surprising after World War I had shaken their confidence in the beneficial outcomes of a global knowledge infrastructure. A complex entanglement of dis-interested management and provincial politics sent the numerous boxes and folders on a long trajectory through Brussels, until they finally slipped out of the city. It is telling that the Capital of Europe has been unable to hold on to its pertinent past. | + | Its tragic demise was unfortunately equally at home in Brussels. Already in Otlet's lifetime, the project fell prey to the dis-interest of its former patrons, not surprising after World War I had shaken their confidence in the beneficial outcomes of a global knowledge infrastructure. A complex entanglement of dis-interested management and provincial politics sent the numerous boxes and folders on a long trajectory through Brussels, until they finally slipped out of the city. It is telling that the Capital of Europe has been unable to hold on to its pertinent past.</div> |

| − | + | [[file:Brussels.jpg]] | |

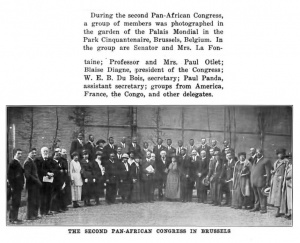

| − | [[ | + | <div class="intro">This tour is a kind of itinerant monument to the Mundaneum in [[Brussels]]. It takes you along the many temporary locations of the archives, guided by the words of care-takers, reporters and biographers that have crossed it's path. Following the increasingly dispersed and dwindling collection through the city and centuries, you won't come across any material trace of its passage. You might discover many unknown corners of Brussels though.</div> |

== 1919: Musée international == | == 1919: Musée international == | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

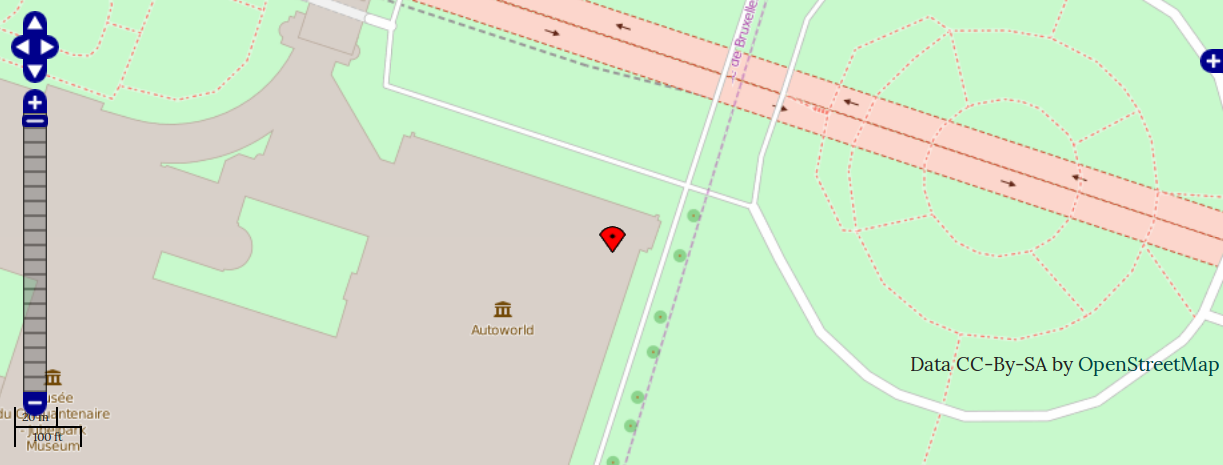

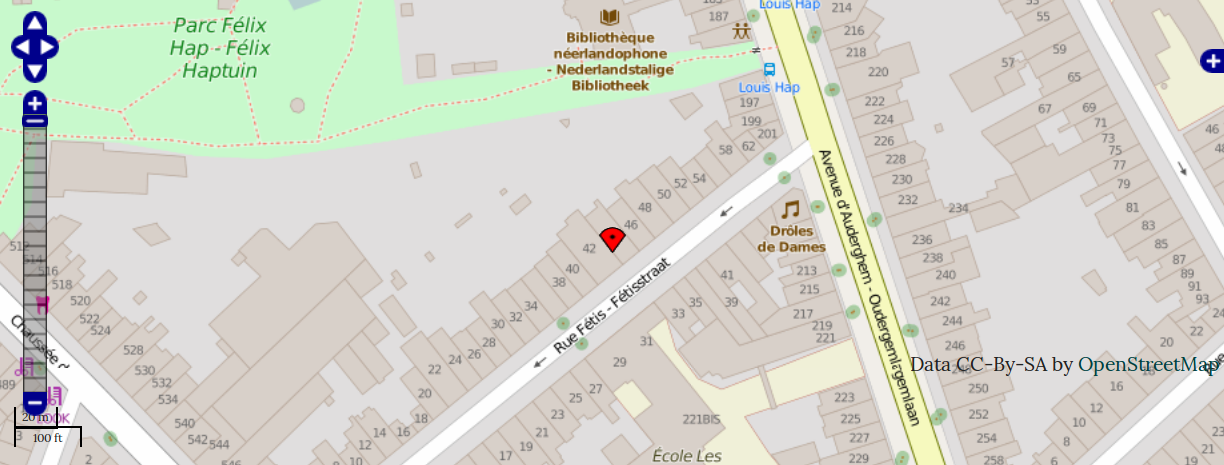

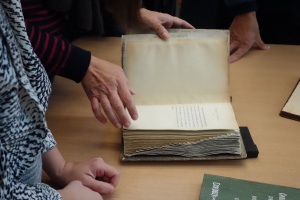

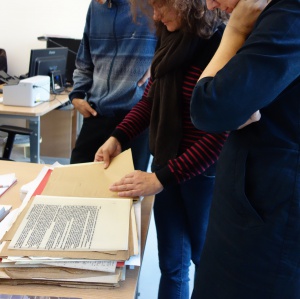

<div class="inter">Part of the archives were moved Rue Fétis, but many boxes and most of the card-indexes remained stored in the Cinquantenaire building. [[Paul Otlet]] continued a vigorous program of lectures and meetings in other places, including at home.</div> | <div class="inter">Part of the archives were moved Rue Fétis, but many boxes and most of the card-indexes remained stored in the Cinquantenaire building. [[Paul Otlet]] continued a vigorous program of lectures and meetings in other places, including at home.</div> | ||

| + | |||

{{#ask: [[place::Rue Fetis 44]] | {{#ask: [[place::Rue Fetis 44]] | ||

| Line 75: | Line 76: | ||

<div class="guide">Exit the Fétisstraat onto Chaussee de Wavre, turn right and follow into the Vijverstraat. Turn right on Rue Gray, cross Jourdan plein into [[Parc Leopold - Avenue du Maelbeek 3|Parc Leopold]]. Right at the entrance is the building of l’Institut d’Anatomie Raoul Warocqué.</div> | <div class="guide">Exit the Fétisstraat onto Chaussee de Wavre, turn right and follow into the Vijverstraat. Turn right on Rue Gray, cross Jourdan plein into [[Parc Leopold - Avenue du Maelbeek 3|Parc Leopold]]. Right at the entrance is the building of l’Institut d’Anatomie Raoul Warocqué.</div> | ||

| − | <div class="inter">In [[Date::1941]], the Nazi-Germans occupying Belgium wanted to use the spaces in the Palais du Cinquantenaire but they were still used to store the collections of the [[Mundaneum]]. They decided to move the archives to Parc Léopold except for a mass of periodicals, which were simply destroyed. A vast quantity of files related to international associations were assumed to have propaganda value for the German war effort. This part of the archive was transferred back to Berlin and apparently re-appeared in the Stanford archives | + | <div class="inter">In [[Date::1941]], the Nazi-Germans occupying Belgium wanted to use the spaces in the Palais du Cinquantenaire but they were still used to store the collections of the [[Mundaneum]]. They decided to move the archives to the former anatomical theatre Raoul Warocqué in Parc Léopold, except for a mass of periodicals, which were simply destroyed. A vast quantity of files related to international associations were assumed to have propaganda value for the German war effort. This part of the archive was transferred back to Berlin and apparently re-appeared in the Stanford archives many years later. They must have been taken there by American soldiers after World War II.</div> |

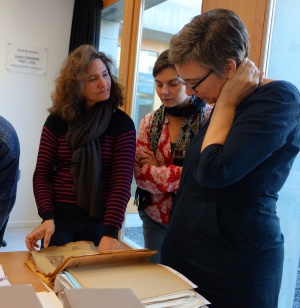

<div class="inter">Until the 1970's, the [[Mundaneum]] (or what was left of it) remained in the decaying building in Parc Léopold. Georges Lorphèvre and [[André Colet]] continued to carry on the work of the Mundaneum with the help of a few now elderly ''Amis du Palais Mondial'', members of the association with the same name that was founded in [[date::1921]]. It is here that the Belgian librarian [[André Canonne]], the Australian scholar [[Warden Boyd Rayward]] and the Belgian documentary-maker [[Françoise Levie]] came across the Mundaneum archives for the very first time.</div> | <div class="inter">Until the 1970's, the [[Mundaneum]] (or what was left of it) remained in the decaying building in Parc Léopold. Georges Lorphèvre and [[André Colet]] continued to carry on the work of the Mundaneum with the help of a few now elderly ''Amis du Palais Mondial'', members of the association with the same name that was founded in [[date::1921]]. It is here that the Belgian librarian [[André Canonne]], the Australian scholar [[Warden Boyd Rayward]] and the Belgian documentary-maker [[Françoise Levie]] came across the Mundaneum archives for the very first time.</div> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 100: | ||

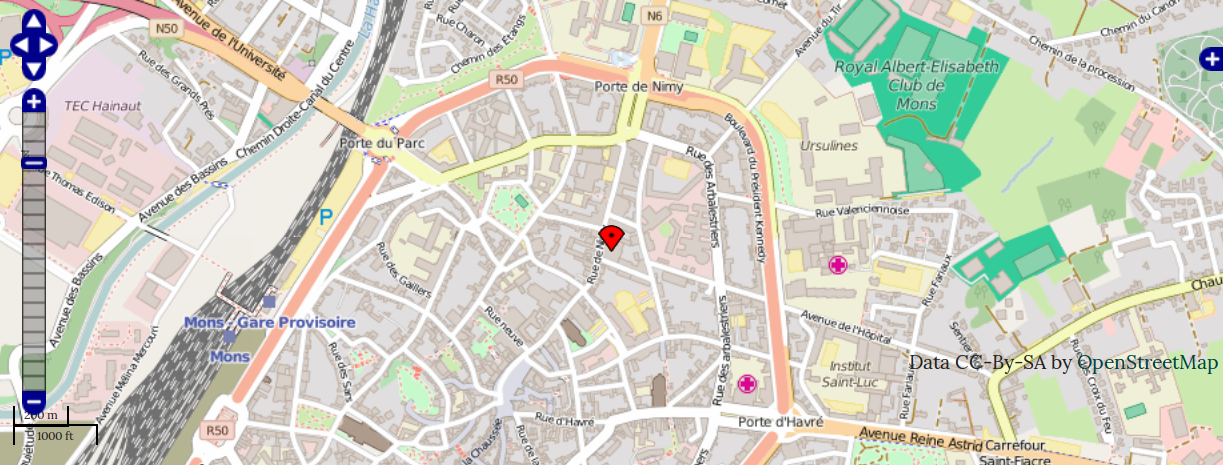

<div class="inter">In 2009, Google Belgium opened its offices at the [[place::Chaussée d'Etterbeek 180]]. It is only a short walk away from the last location that Paul Otlet has been able to work on the [[Mundaneum]] project.</div> | <div class="inter">In 2009, Google Belgium opened its offices at the [[place::Chaussée d'Etterbeek 180]]. It is only a short walk away from the last location that Paul Otlet has been able to work on the [[Mundaneum]] project.</div> | ||

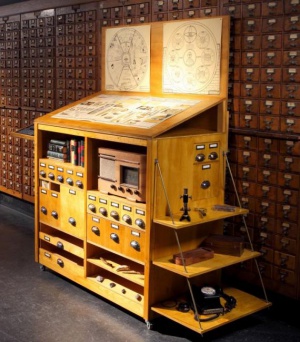

| − | <div class="inter">Celebrating the discovery of its "European roots", the company has insisted on the connection between the project of Paul Otlet, and their own mission to ''organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful''. To celebrate the desired connection to the Forefather of documentation, the building is said to have a Mundaneum meeting room. | + | <div class="inter">Celebrating the discovery of its "European roots", the company has insisted on the connection between the project of Paul Otlet, and their own mission to ''organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful''. To celebrate the desired connection to the Forefather of documentation, the building is said to have a Mundaneum meeting room. For some time you could apparently find a vitrine in the lobby with one of the drawers filled with UDC-index cards, on loan from the Mundaneum archive center in Mons.</div> |

| − | |||

{{#ask: [[place::Chaussée d'Etterbeek 180]] | {{#ask: [[place::Chaussée d'Etterbeek 180]] | ||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

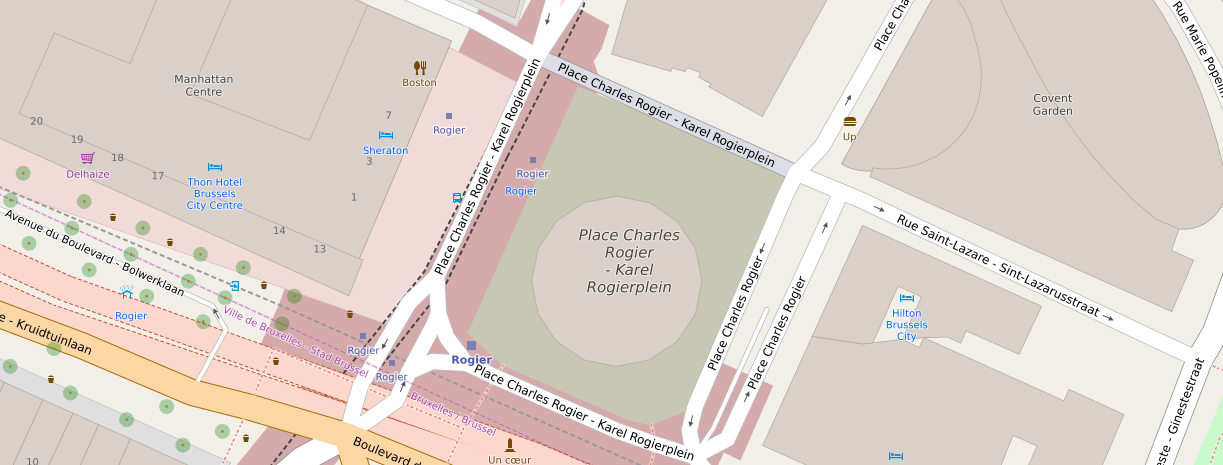

== 1985: Espace Mundaneum under Place Rogier == | == 1985: Espace Mundaneum under Place Rogier == | ||

| − | [[file: | + | [[file:place_rogier.png]] |

<div class="quote"> | <div class="quote"> | ||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

<div class="guide">(from Place Rogier, ca. 30") Follow Boulevard du Jardin Botanique and turn left onto Adolphe Maxlaan and Place De Brouckère. Continue onto Anspachlaan, turn right onto Rue du Marché aux Poulets. Turn left onto Visverkopersstraat and continue onto Rue Van Artevelde. Continue straight onto Anderlechtschesteenweg, continue onto Chaussée de Mons. Turn left onto Otletstraat. Alternatively you can take tram 51 or 81 to Porte D'Anderlecht.</div> | <div class="guide">(from Place Rogier, ca. 30") Follow Boulevard du Jardin Botanique and turn left onto Adolphe Maxlaan and Place De Brouckère. Continue onto Anspachlaan, turn right onto Rue du Marché aux Poulets. Turn left onto Visverkopersstraat and continue onto Rue Van Artevelde. Continue straight onto Anderlechtschesteenweg, continue onto Chaussée de Mons. Turn left onto Otletstraat. Alternatively you can take tram 51 or 81 to Porte D'Anderlecht.</div> | ||

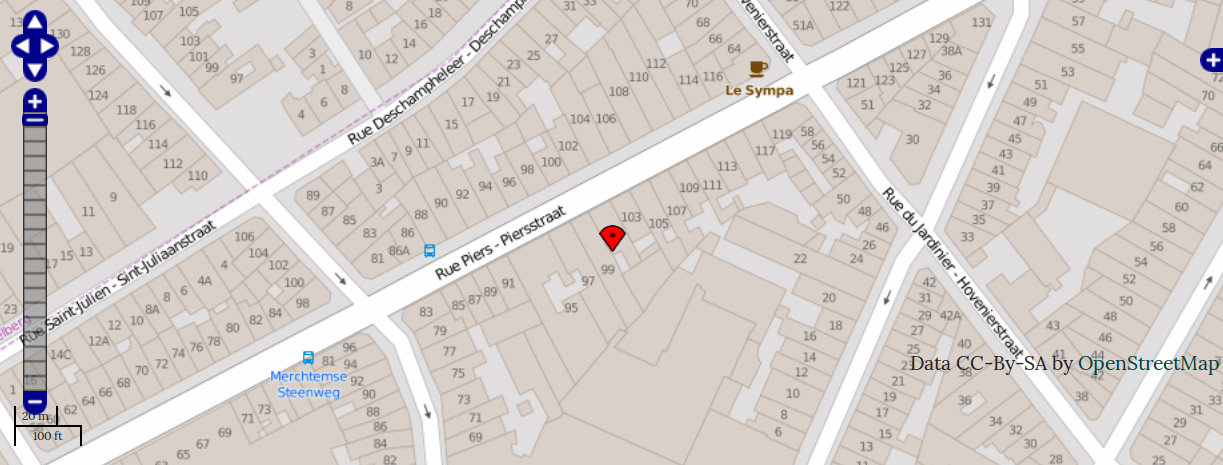

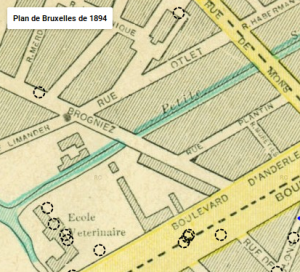

| − | <div class="inter">Although it seems that this dreary street is named to honor Paul Otlet, it already mysteriously appears on a map dated 1894 when Otlet was not even 26 years old <ref>http://www.reflexcity.net/bruxelles/plans/4-cram-fin-xixe.html</ref> and again on a map from 1910, when the Mundaneum had not yet opened it's doors.<ref>http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84598749/f1.item.zoom</ref></div> | + | <div class="inter">Although it seems that this dreary street is named to honor Paul Otlet, it already mysteriously appears on a map dated 1894 when Otlet was not even 26 years old <ref>http://www.reflexcity.net/bruxelles/plans/4-cram-fin-xixe.html</ref> and again on a map from 1910, when the Mundaneum had not yet opened it's doors. The street is probably named after Otlet's father, the entrepreneur ("Le roi du tramways") and senator Edouard Otlet who died in 1907.<ref>http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84598749/f1.item.zoom</ref></div> |

Latest revision as of 09:20, 23 September 2016

1919: Musée international

Outre le Répertoire bibliographique universel et un Musée de la presse qui comptera jusqu’à 200.000 spécimens de journaux du monde entier, on y trouvera quelque 50 salles, sorte de musée de l’humanité technique et scientifique. Cette décennie représente l’âge d’or pour le Mundaneum, même si le gros de ses collections fut constitué entre 1895 et 1914, avant l’existence du Palais Mondial. L’accroissement des collections ne se fera, par la suite, plus jamais dans les mêmes proportions.[1]

En 1920, le Musée international et les institutions créées par Paul Otlet et Henri La Fontaine occupent une centaine de salles. L’ensemble sera désormais appelé Palais Mondial ou Mundaneum. Dans les années 1920, Paul Otlet et Henri La Fontaine mettront également sur pied l’Encyclopedia Universalis Mundaneum, encyclopédie illustrée composée de tableaux sur planches mobiles.[2]

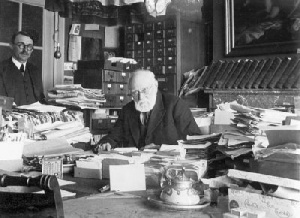

1934: Mundaneum moved to home of Paul Otlet

Si dans de telles conditions le Palais Mondial devait définitivement rester fermé, il semble bien qu’il n’y aurait plus place dans notre Civilisation pour une institution d’un caractère universel, inspirée de l’idéal indiqué en ces mots à son entrée : Par la Liberté, l’Égalité et la Fraternité mondiales − dans la Foi, l’Espérance et la Charité humaines − vers le Travail, le Progrès et la Paix de tous ![3]

Cato, my wife, has been absolutely devoted to my work. Her savings and jewels testify to it; her invaded house testify to it; her collaboration testifies to it; her wish to see it finished after me testifies to it; her modest little fortune has served for the constitution of my work and of my thought.[4]

1941: Mundaneum in Parc Léopold

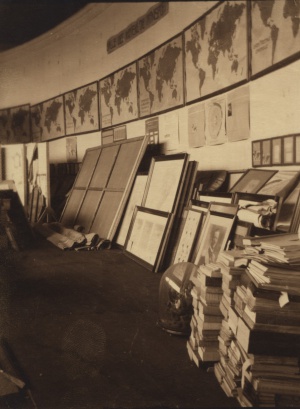

The upper galleries ... are one big pile of rubbish, one inspector noted in his report. It is an impossible mess, and high time for this all to be cleared away. The Nazis evidently struggled to make sense of the curious spectacle before them. The institute and its goals cannot be clearly defined. It is some sort of ... 'museum for the whole world,' displayed through the most embarrassing and cheap and primitive methods.[5]

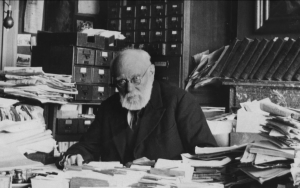

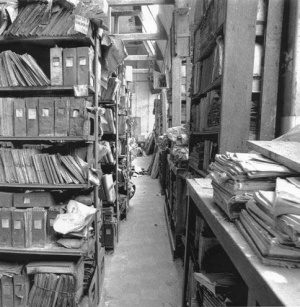

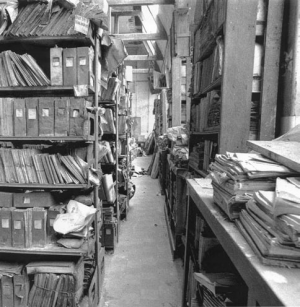

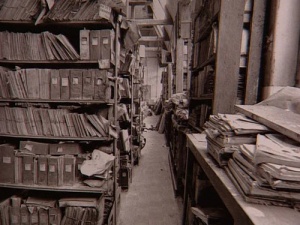

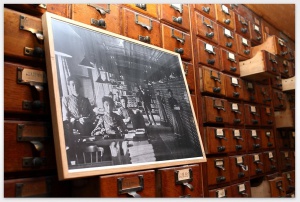

Distributed in two large workrooms, in corridors, under stairs, and in attic rooms and a glass-roofed dissecting theatre at the top of the building, this residue gradually fell prey to the dust and damp darkness of the building in its lower regions, and to weather and pigeons admitted through broken panes of glass in the roof in the upper rooms. On the ground floor of the building was a dimly lit, small, steeply-raked lecture theatre. On either side of its dais loomed busts of the founders.[6]

Derrière les vitres sales, j’aperçus un amoncellement de livres, de liasses de papiers contenus par des ficelles, des dossiers dressés sur des étagères de fortune. Des feuilles volantes échappées des cartons s’amoncelaient dans les angles de l’immense pièce, du papier pelure froissé se mêlait au gravat et à la poussière. Des récipients de fortune avaient été placés entre les caisses et servaient à récolter l’eau de pluie. Un pigeon avait réussi à pénétrer à l’intérieur et se cognait inlassablement contre l’immense baie vitrée qui fermait le bâtiment.[7]

Annually in this room in the years after Otlet's death until the late 1960's, the busts garlanded with floral wreaths for the occasion, Otlet and La Fontaine's colleagues and disciples, Les Amis du Palais Mondial, met in a ceremony of remembrance. And it was Otlet, theorist and visionary, who held their imaginations most in beneficial thrall as they continued to work after his death, just as they had in those last days of his life, among the mouldering, discorded collections of the Mundaneum, themselves gradually overtaken by age, their numbers dwindling.[8]

2009: Offices Google Belgium

A natural affinity exists between Google's modern project of making the world’s information accessble and the Mundaneum project of two early 20th century Belgians. Otlet and La Fontaine imagined organizing all the world's information - on paper cards. While their dream was discarded, the Internet brought it back to reality and it's little wonder that many now describe the Mundaneum as the paper Google. Together, we are showing the way to marry our paper past with our digital future. [9]

1944: Grave of Paul Otlet

When I am no more, my documentary instrument (my papers) should be kept together, and, in order that their links should become more apparent, should be sorted, fixed in successive order by a consecutive numbering of all the cards (like the pages of a book).[10]

Je le répète, mes papiers forment un tout. Chaque partie s’y rattache pour constituer une oeuvre unique. Mes archives sont un "Mundus Mundaneum", un outil conçu pour la connaissance du monde. Conservez-les; faites pour elles ce que moi j’aurais fait. Ne les détruisez pas ! [11]

1981: Storage at Avenue Rogier 67

C'est à ce moment que le conseil d'administration, pour sauver les activités (expositions, prêts gratuits, visites, congrès, exposés, etc.) vendit quelques pièces. Il n'y a donc pas eu de vol de documents, contrairement à ce que certains affirment, garantit de Louvroy.[12]

In fact, not one of the thousands of objects contained in the hundred galleries of the Cinquantenaire has survived into the present, not a single maquette, not a single telegraph machine, not a single flag, though there are many photographs of the exhibition rooms.[13]

Mais je me souviens avoir vu à Bruxelles des meubles d'Otlet dans des caves inondées. On dit aussi que des pans entiers de collections ont fait le bonheur des amateurs sur les brocantes. Sans compter que le papier se conserve mal et que des dépôts mal surveillés ont pollué des documents aujourd'hui irrécupérables.[14]

1985: Espace Mundaneum under Place Rogier

On peut donc croire sauvées les collections du "Mundaneum" et a bon droit espérer la fin de leur interminable errance. Au moment ou nous écrivons ces lignes, des travaux d’aménagement d'un "Espace Mundaneum" sont en voie d’achèvement au cour de Bruxelles.[16]

L'acte fut signé par le ministre Philippe Monfils, président de l'exécutif. Son prédécesseur, Philippe Moureaux, n'était pas du même avis. Il avait même acheté pour 8 millions un immeuble de la rue Saint-Josse pour y installer le musée. Il fallait en effet sauver les collections, enfouies dans l'arrière-cour d'une maison de repos de l'avenue Rogier! (...) L'étage moins deux, propriété de la commune de Saint-Josse, fut cédé par un bail emphytéotique de 30 ans à la Communauté, avec un loyer de 800.000 F par mois. (...) Mais le Mundaneum est aussi en passe de devenir une mystérieuse affaire en forme de pyramide. A l'étage moins un, la commune de Saint-Josse et la société française «Les Pyramides» négocient la construction d'un Centre de congrès (il remplace celui d'un piano-bar luxueux) d'ampleur. Le montant de l'investissement est évalué à 150 millions (...) Et puis, ce musée fantôme n'est pas fermé pour tout le monde. Il ouvre ses portes! Pas pour y accueillir des visiteurs. On organise des soirées dansantes, des banquets dans la grande salle. Deux partenaires (dont un traiteur) ont signé des contrats avec l'ASBL Centre de lecture publique de la communauté française. Contrats reconfirmés il y a quinze jours et courant pendant 3 ans encore![17]

Mais curieusement, les collections sont toujours avenue Rogier, malgré l'achat d'un local rue Saint-Josse par la Communauté française, et malgré le transfert officiel (jamais réalisé) au «musée» du niveau - 2 de la place Rogier. Les seules choses qu'il contient sont les caisses de livres rétrocédées par la Bibliothèque Royale qui ne savait qu'en faire.[18]

You can end the tour here, or add two optional destinations:

1934: Imprimerie van Keerberghen in Rue Piers

Rue Otlet

Outside Brussels

1998: The Mundaneum resurrected

Bernard Anselme, le nouveau ministre-président de la Communauté française, négocia le transfert à Mons, au grand dam de politiques bruxellois furieux de voir cette prestigieuse collection quitter la capitale. (...) Cornaqué par Charles Picqué et Elio Di Rupo, le transfert à Mons n'a pas mis fin aux ennuis du Mundaneum. On créa en Hainaut une nouvelle ASBL chargée d'assurer le relais. C'était sans compter avec l'ASBL Célès, héritage indépendant du CLPCF, évoqué plus haut, que la Communauté avait fini par dissoudre. Cette association s'est toujours considérée comme propriétaire des collections, au point de s'opposer régulièrement à leur exploitation publique. Les faits lui ont donné raison: au début du mois de mai, le Célès a obtenu du ministère de la Culture que cinquante millions lui soient versés en contrepartie du droit de propriété.[21]

The reestablishment of the Mundaneum in Mons as a museum and archive is in my view a major event in the intellectual life of Belgium. Its opening attracted considerable international interest at the time.[22]

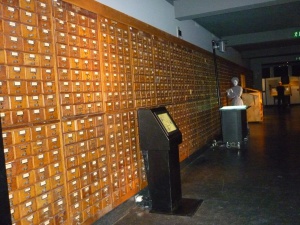

Le long des murs, 260 meubles-fichiers témoignaient de la démesure du projet. Certains tiroirs, ouverts, étaient éclairés de l’intérieur, ce qui leur donnait une impression de relief, de 3D. Un immense globe terrestre, tournant lentement sur lui-même, occupait le centre de l’espace. Sous une voie lactée peinte à même le plafond, les voix de Paul Otlet et d’Henri La Fontaine, interprétés par des comédiens, s’élevaient au fur et à mesure que l’on s’approchait de tel ou tel document.[23]

L’Otletaneum, c’est à dire les archives et papiers personnels ayant appartenu à Paul Otlet, représentait un fonds important, peu connu, mal répertorié, que l’on pouvait cependant quantifier à la place qu’il occupait sur les étagères des réserves situées à l’arrière du musée. Il y avait là 100 à 150 mètres de rayonnages, dont une partie infime avait fait l’objet d’un classement. Le reste, c’est à dire une soixantaine de boîtes à bananes‚ était inexploré. Sans compter l’entrepôt de Cuesmes où le travail de recensement pouvait être estimé, me disait-il, à une centaine d’années...[24]

Après des multiples déménagements, un travail laborieux de sauvegarde entamé par les successeurs, ce patrimoine unique ne finit pas de révéler ses richesses et ses surprises. Au-delà de cette démarche originale entamée dans un esprit philanthropique, le centre d’archives propose des collections documentaires à valeur historique, ainsi que des archives spécialisées.[25]

2007: Crystal computing

Jean-Paul Deplus, échevin (adjoint) à la culture de la ville, affiche ses ambitions. « Ce lieu est une illustration saisissante de ce que des utopistes visionnaires ont apporté à la civilisation. Ils ont inventé Google avant la lettre. Non seulement ils l’ont fait avec les seuls outils dont ils disposaient, c’est-à- dire de l’encre et du papier, mais leur imagination était si féconde que l’on a retrouvé les dessins et croquis de ce qui préfigure Internet un siècle plus tard. » Et Jean-Pol Baras d’ajouter «Et qui vient de s’installer à Mons ? Un “data center” de Google ... Drôle de hasard, non ? » [26]

Dans une ambiance où tous les partenaires du «projet Saint-Ghislain» de Google savouraient en silence la confirmation du jour, les anecdotes sur la discrétion imposée durant 18 mois n’ont pas manqué. Outre l’utilisation d’un nom de code, Crystal Computing, qui a valu un jour à Elio Di Rupo d’être interrogé sur l’éventuelle arrivée d’une cristallerie en Wallonie («J’ai fait diversion comme j’ai pu !», se souvient-il), un accord de confidentialité liait Google, l’Awex et l’Idea, notamment. «A plusieurs reprises, on a eu chaud, parce qu’il était prévu qu’au moindre couac sur ce point, Google arrêtait tout»[27]

Beaucoup de show, peu d’emplois: Pour son data center belge, le géant des moteurs de recherche a décroché l’un des plus beaux terrains industriels de Wallonie. Résultat : à peine 40 emplois directs et pas un euro d’impôts. Reste que la Région ne voit pas les choses sous cet angle. En janvier, a appris Le Vif/L’Express, le ministre de l’Economie Jean-Claude Marcourt (PS) a notifié à Google le refus d’une aide à l’expansion économique de 10 millions d’euros. Motif : cette aide était conditionnée à la création de 110 emplois directs, loin d’être atteints. Est-ce la raison pour laquelle aucun ministre wallon n’était présent le 10 avril aux côtés d’Elio Di Rupo ? Au cabinet Marcourt, on assure que les relations avec l’entreprise américaine sont au beau fixe : « C’est le ministre qui a permis ce nouvel investissement de Google, en négociant avec son fournisseur d’électricité (NDLR : Electrabel) une réduction de son énorme facture.[28]

- ↑ Paul Otlet (1868-1944) Fondateur du mouvement bibliogique international Par Jacques Hellemans (Bibliothèque de l’Université libre de Bruxelles, Premier Attaché)

- ↑ Jacques Hellemans. Paul Otlet (1868-1944) Fondateur du mouvement bibliogique international

- ↑ Paul Otlet. Document II in: Traité de documentation (1934)

- ↑ Paul Otlet. Diary (1938), Quoted in: W. Boyd Rayward. The Universe of Information : The Work of Paul Otlet for Documentation and International Organisation (1975)

- ↑ Alex Wright. Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age (2014)

- ↑ Warden Boyd Rayward. Mundaneum: Archives of Knowledge (2010)

- ↑ Françoise Levie. L'homme qui voulait classer le monde: Paul Otlet et le Mundaneum (2010)

- ↑ Warden Boyd Rayward. Mundaneum: Archives of Knowledge (2010)

- ↑ William Echikson. A flower of computer history blooms in Belgium (2013) http://googlepolicyeurope.blogspot.be/2013/02/a-flower-of-computer-history-blooms-in.html

- ↑ Testament Paul Otlet, 1942.01.18*, No. 67, Otletaneum. Quoted in: W. Boyd Rayward. The Universe of Information : The Work of Paul Otlet for Documentation and International Organisation (1975)

- ↑ Paul Otlet cited in Françoise Levie, Filmer Paul Otlet, Cahiers de la documentation – Bladen voor documentatie – 2012/2

- ↑ Le Soir, 27 juillet 1991

- ↑ Warden Boyd Rayward. Mundaneum: Archives of Knowledge (2010)

- ↑ Le Soir, 17 juin 1998

- ↑ http://www.reflexcity.net/bruxelles/photo/72ca206b2bf2e1ea73dae1c7380f57e3

- ↑ André Canonne. Introduction to the 1989 facsimile edition of Le Traité de documentation File:TDD ed1989 preface.pdf

- ↑ Le Soir, 24 juillet 1991

- ↑ Le Soir, 27 juillet 1991

- ↑ http://www.reflexcity.net/bruxelles/plans/4-cram-fin-xixe.html

- ↑ http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84598749/f1.item.zoom

- ↑ Le Soir, 17 juin 1998

- ↑ Warden Boyd Rayward. Mundaneum: Archives of Knowledge (2010)

- ↑ Françoise Levie, Filmer Paul Otlet, Cahiers de la documentation – Bladen voor documentatie – 2012/2

- ↑ Françoise Levie, L'Homme qui voulait classer le monde: Paul Otlet et le Mundaneum, Impressions Nouvelles, Bruxelles, 2006

- ↑ Stéphanie Manfroid, Les réalités d’une aventure documentaire, Cahiers de la documentation – Bladen voor documentatie – 2012/2

- ↑ Jean-Michel Djian, Le Mundaneum, Google de papier, Le Monde Magazine, 19 december 2009

- ↑ Libre Belgique (27 april 2007)

- ↑ Le Vif, April 2013

- ↑ Le Vif, April 2013

- ↑ http://www.rtbf.be/info/regions/detail_google-va-investir-300-millions-a-saint-ghislain?id=7968392